David Cameron has spent the last week discussing the UK’s role within the European Union. Photo by the UK Department for International Development, freely licensed under CC BY 2.0.

It’s a question that has been nagging at the British public for years—now, they’ll vote on it.

David Cameron announced on Saturday, February 20, that the United Kingdom would vote on whether to remain in the European Union on June 23 of this year—an announcement which came hours after he secured concessions on his country’s status within the union.

Wikipedia’s article on the upcoming referendum has existed since November 2012, under the title “Brexit”—the neologism used in the British press to refer to a “British exit” from the EU. Similar terms, like “Grexit” for Greece and “Spexit” for Spain, are less frequently used and abused.

Back then, it was a concept long bandied around by fringe parties. Most notable of these is the UK Independence Party (UKIP), a “Eurosceptic” party whose primary aim is to get the UK out of the Union. While they have a number of representatives in the European Parliament, they had no real sway in domestic politics.

Until, that is, 2015 general election. There, they gathered 12.6% of the popular vote and won their first seat in the House of Commons. It signalled that the UK was starting to open up to the idea of leaving the EU, something seen as almost impossible only a few years ago.

In articles like these, it can be difficult for Wikipedia editors to keep tabs on edits to the various affected pages. We spoke to Katherine Bavage, who has edited the English Wikipedia for almost four years and is a staff member at Wikimedia UK, the independent Wikimedia chapter in the United Kingdom.

Bavage explains that editors must keep a close eye on policies, especially with regards to biographies of living persons, during times of potential political conflict.

“[Major political events] increase traffic to specific pages and can boost new page creation—some good, some bad,” she says. “There’s a tendency to create pages that may lack long term notability, and often not enough work on the ‘nuts and bolts’ of better categorising and organising pages to increase discoverability.

“There’s also a lot of work for hard-pressed admins trying to enforce biography of living persons policy in an environment where people might not be approaching editing in a neutral way.”

In the past few weeks, as part of the fulfilment of his electoral manifesto, UK Prime Minister David Cameron has discussed terms with various EU leaders—most notably with current President of the European Council, Donald Tusk. The onset of the migrant crisis in Europe, as well as Greece’s need for a bailout last year, influenced Cameron’s demands.

On Saturday, a deal was reached, providing the UK with special status as a part of the Union. While it wasn’t as good as Cameron was targeting, he’ll hope the “emergency brake” on migrant work benefits, more protection for the UK’s currency, and an opt-out of the “ever-closer union” phrasing will be enough to persuade the British public to side with him in June.

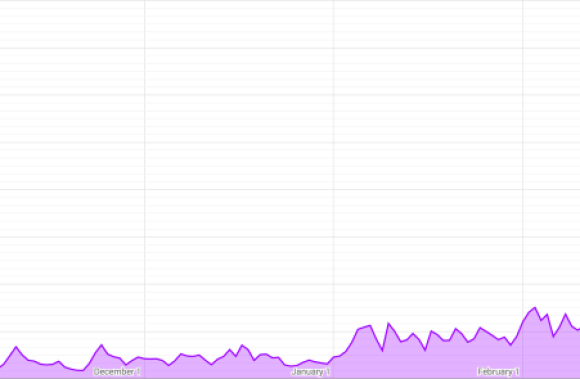

Views on the referendum article peaked as David Cameron unveiled the date. Image by Joe Sutherland, public domain.

Following the announcement of the referendum date, the article’s view counts spiked. It went from an average of 1,300 views to a one-day peak of 14,400, helped somewhat by intense media coverage across Europe. We expect it to increase further as the referendum draws near.

The article was quickly updated to reflect the date, with a move from “United Kingdom European Union membership referendum” to its current title. It has attracted more than 200 edits since the announcement, at lunchtime on Saturday.

Its content is as such quite new, and likely to develop rapidly as campaigns march on. “There’s probably an argument to be made to separate out what is history and what is the referendum campaign, with links to tables and other resources such as polling data and open data sets that can be referenced by either side,” Bavage says.

“The challenge in enforcing neutrality will be not just ensuring statements are referenced but that there is a balance of statements put forward,” she adds. “WikiProjects have a role to play here, as do all politically-minded editors.”

While the Prime Minister will campaign to stay in the EU, it is thought almost half of his party’s members of parliament will do the opposite, along with UKIP and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party. However, the rest of the House of Commons—including Labour, the official opposition—will likely side with Cameron.

As chronicled by Wikipedia, polling has been taking place on this issue since 2010, and has shown the issue to be divisive. While polls vary dramatically by country (Scotland and Northern Ireland tend to be strongly pro-union, while England and Wales are more open to leaving), it is otherwise difficult to call.

Whatever the result of the vote, Wikipedians will be standing by, ready to update the article at a moment’s notice.

Joe Sutherland, Communications Intern

Wikimedia Foundation

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation