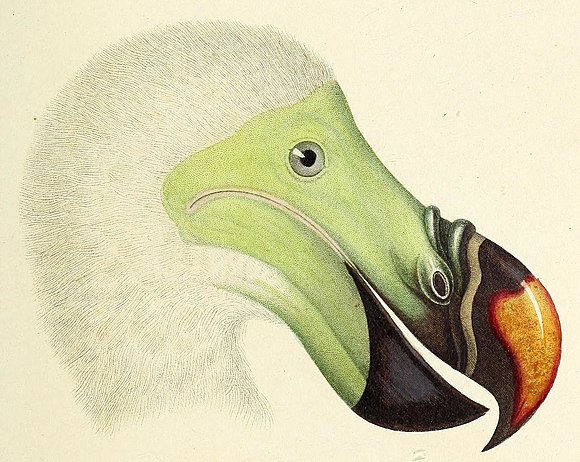

One millionth image—the head of a Dodo. Illustration from “Atlas de Zoologie” (1844) by Paul Gervais. Originally scanned by the Natural History Museum, London, public domain

Over the past three years, my volunteer time has been devoted to releasing free cultural and historical imagery on the Wikimedia Commons. My part-time hobby—relying on a cheap netbook and an old but trusty Macmini home desktop—has reached 1,000,000 diverse and high quality images for public reuse, carrying with it a massive long term educational impact. The milestone makes this a good moment to highlight a handful of interesting projects and gives an insight into the experience of being a Wikimedia Commons batch uploader, pointing to the methods used to help anyone interested in having a go.

Los Angeles County Museum of Public Art

The LACMA upload of 25,000 high resolution photographs of museum artwork was started in July 2013, and 500 volunteers have contributed to the categorization and reuse of images. The upload relied on a custom Python program to take information from the LACMA website and create the image page text, with some catalogue entries having several useful photographs of the same museum object. Most of the programming time was spent debugging how to get Japanese and Chinese characters used in the museum’s descriptions to display correctly on Commons. Anyone using Python to take data from international websites is going to face the challenge of changing formats between different web standards and languages.

As this was my first serious attempt to use Python scripts to release a large number of images, it took about three months of experimenting and testing before I felt safe enough to do a final run; I was helped by the “beta” version of Commons, which is a safe “non-production” space where your uploads and changes will not harm other projects.

A current experiment reusing these uploaded images, attempts to test the public impact of posting the collection to this Flickr group (using Flickr’s free programming interface). The experiment checks which images are most popular, or reused, compared to those hosted on Wikimedia Commons, and whether this form of sharing results in viewers following the links back to Commons. It is hoped to demonstrate the value of co-releasing Wikimedia Commons media with good quality metadata on Flickr and/or other free channels hosting image, audio and video.

LGBT Free Media Collective

The idea of the LGBT Free Media Collective was to encourage more uploads of LGBT-related free media of historic and cultural interest, as LGBT culture is under-represented on Wikimedia Commons; there are few archives of photographs with expired copyright that are relevant. The volunteer network and its IRC channel, which started in this 2012 event, was a precursor to formalizing the Wikimedia LGBT+ official user group and supporting the series of highly successful Wiki Loves Pride events around the world—an annual event that continues today.

Uploads included several thousand photographs from a large number of Flickr accounts, ensuring excellent global coverage of the LGBT Pride movement’s impact. Methods have included using the simple Flickr2commons tool through to custom uploads relying on the Flickr API.

If you have taken photographs of LGBT+ cultural events, this gives an easy way of sharing them and getting better public reuse than just keeping your best photographs on Flickr or Facebook.

Medical history scans from Wellcome Images

At the end of 2014, 100,000 high resolution images from the Wellcome Library—an institution devoted to the history of medicine—were released on Wikimedia Commons after several meetings and discussions I had with the library over a period of two years. The library changed from defaulting to a non-commercial copyright restriction to allowing full free use for all of its scanned historic medical images. The in-person meetings had another benefit as well: when it came time to mass upload the images, they were kind enough to provide me with a hard disk with over 300 GB of files to avoid file-by-file manual downloads (along with their website’s bot-resisting formatting). For an upload of this size, it is possible for the Wikimedia Foundation to upload files directly. In this particular case, a disk was lost in the mail, so to avoid any other mishaps, I used my home broadband connection and netbook. They took around two months (eight weeks) to upload.

You can read more about this project in my blog post from last January. More recently, Wikimedia UK gave the Wellcome Library a “Wiki

partnership of 2015” award, partially in recognition of the importance

of this project.

Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA)

This upload is still ongoing: it runs a couple of times a year on request as more photographs are published on SuSanA’s Flickr account. Over 10,000 photographs have been released on Wikimedia Commons, with over 200 volunteers helping to categorize them. This partnership is a good example of how Wikimedia volunteers can work to the benefit of unrelated organizations, NGOs (non-governmental organizations), charities etc. at zero-cost, increase the educational value of Wikimedia Commons, and help illustrate health related Wikipedia articles. SuSanA is a loose network or alliance of organizations active in the field of sustainable sanitation. The photographs are for example showing how to build low-cost hygienic and sustainable toilet facilities in developing countries, ensuring that some of the poorest people in the world are safer from disease, have access to unpolluted water and recycle their excreta to create more fertile soil for farming.

You can find the source code for free reuse here on github.

Historic American Buildings Survey

The largest single upload project happened when I was exploring different high-quality photograph collections in the Library of Congress archives.

The HABS archive is maintained by the U.S. National Parks Service, being a continuous set of survey records and photographs spanning over a hundred years for buildings and sites of historic interest in America. 300,000 photographs were uploaded, along with their map coordinates, with significant testing going into ensuring suitable categories were added for the different sites, along with most of the information carried over from the Library of Congress catalogues. Fortunately there is a consistent system of site numbering (the National Register of Historic Places) and this reduces confusion for how best to name or structure categories.

The GLAMwiki toolset was newly available to perform the huge number of image file uploads, so this became a flagship example of how large uploads could use the tool. Most of the “real work” is structuring the metadata that goes to create the image text pages, but not having to pass all the images through my home broadband is a great improvement!

The images have been useful and popular, especially due to the cross-over with Wiki Loves Monuments, so that new photographs can be compared with archive shots from decades earlier. An amazing 1,400 Commons volunteers have supported the project with categorization and improvements.

Conclusion

Getting to a million educational images—which is 4% of all of the files on Wikimedia Commons—has been a personal marathon. I have been busy creating new tools, learning how to write in Python, navigating the Wikimedia Commons API and improving project guidelines. Still, this is a hugely rewarding hobby; you could have the chance to become part of an open knowledge community, the experience of working with major educational and cultural institutions, and seeing your volunteer time have direct outcomes to improve educational resources world-wide. For these selfish reasons, I hope this is just my first million!

If these case studies have whetted your appetite for contributing to Wikimedia Commons, there is a set of helpful links here. When you are ready to try uploading larger collections of files, please first read the guide to batch uploading to avoid frequent pitfalls!

Fæ / Ashley Van Haeften

Wikimedia Commons volunteer

Editor’s note: this post was updated after publication due to community comments.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation