As the 31st Summer Olympic Games kick off in Rio de Janeiro, two marathoners from the first modern Olympics lead a parade of great sports stories on Wikipedia.

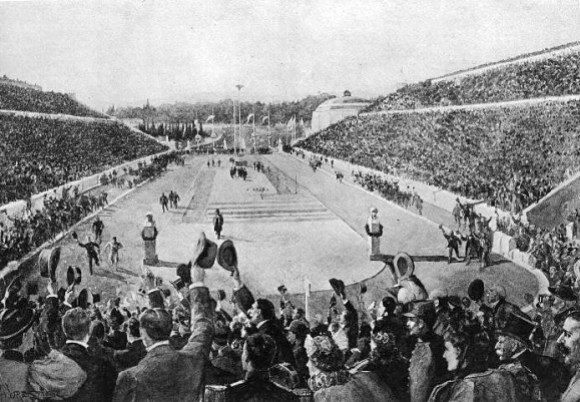

Fifteen centuries after the Roman empire crushed the Olympics, the 1896 Games inspired the world. Unlike in the ancient events, where only men who spoke Greek were permitted to participate, 14 nations were registered to participate. Greece enthusiastically volunteered to host, and a congress was held in Paris to plan. The nations spent 3,740,000 gold drachmas on the Games (more than $12 million USD today), including renovating 80,000-seat Panathinaiko Stadium, first used to hold horse races in the sixth century BC.

Included in the new Games were competitions in fencing, gun shooting, swimming, and tennis, as well as the classical tests of athleticism, such as running, wrestling, and the discus.

And then, none of the Greeks won. The organizers’ slow-creeping embarrassment peaked as every athletic event—the discus throw, in particular—was dominated, one by one, by foreign countries. Desperate for a win from one of their own, the disappointed Greek public turned to Spyridon Louis, a water-carrier from neighboring Amarousio, a town that dates back to the era of the ancient Athenian Republic.

Frenchman Albin Lermusiaux maintained first place for 32 kilometers (19.9 miles). Despite the stress his countrymen felt, Louis was confident and clearly unbothered; while Lermusiaux held the lead, Louis took a break at an inn in the town of Pikermi to enjoy a glass of wine. After asking for status on the race, he declared he would overtake them all before the end.

He did.

Lermusiaux buckled from exhaustion, and Louis—perhaps inspired by ancient Bacchus—swept past the remaining runners without incident, completing the race in 2 hours and 58 minutes. At the finish line in the stadium, he was greeted by Greek princes, showered with gifts, and declared a national hero.

“That hour was something unimaginable,” he recalled, forty years after the victory. “Flowers were raining down on me. Everybody was calling out my name and throwing their hats in the air…”

When all the celebrations were over, he returned to his hometown with a brand-new carriage for his water-carrying business. For decades he remained a celebrity in Greece, and is still one of the most famous people from his town.

But while Spyridon went down in history a hero, another marathoner of the 1896 Olympics went virtually unrecognized. Although the competition excluded women, Stamata Revithi was the first woman to participate – by any means necessary. The Games excluded women from competition, but Revithi insisted that she be allowed to run.

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the International Olympic Committee and father of the modern Olympics, was frank in his disapproval of women athletes; he believed that “contact with women’s athletics is bad [for the male athlete.]” As such, Revithi was not allowed to participate.

She ran anyway.

On the morning of the race she was turned away, and a male runner teased her for daring to show up. In response, she said that she would not insult women, since Greek athletes had already been humiliated in many more events by the Americans.

The next morning, after gathering a host of witnesses, Revithi ran a marathon of her own in 5 and a half hours. She was not allowed to run to the finish line in Panathinaiko Stadium, where an audience of thousands cheered for Spyridon Louis just one day earlier.

No records exist of Ravithi’s life after the race. As Olympic historian Athanasios Tarasouleas stated, “Stamata Revithi was lost in the dust of history,” but her grandstand would inspire a new generation of women runners.

At the 1984 Summer Olympics, 88 years after Ravithi, women would officially be permitted to run the Olympic marathon.

Learn more

Wikipedia is home to a treasure trove of elusive Olympic history. The main Olympics Games article is “featured,” meaning it has successfully moved through an extensive peer review from other Wikipedia editors, and the site’s Did you know section holds many pearls of knowledge:

- Did you know … that the 1984 Olympic Games in Sarajevo was the first since 1932 to make a profit?

- … that the Duchess of Westminster was one of only two women to compete in sailing at the 1908 Summer Olympics?

- …that cars were brought into the Empire Stadium venue to illuminate the last two decathlon events at the 1948 Summer Olympics?

- … that Parry O’Brien won the gold medal in the men’s shot put at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki as part of a four-year long streak in which he won 116 consecutive meets and set 17 world records?

- … that Alan Phillips wasn’t allowed to compete in badminton for South Africa in the 1992 Olympics because he was too old at 36, but he played baseball in the 2000 Olympics at 44?

- … that after Irishman Con O’Kelly won a gold medal for Great Britain at the 1908 Summer Olympics, he was paraded through Hull on the back of a fire engine?

- … that David Bond took eight weeks of unpaid leave from his job in order to become one of three gold medallists for the British team at the 1948 Summer Olympics?

- … that the wrestling match between Alfred Asikainen and Martin Klein at the 1912 Summer Olympics lasted eleven hours and forty minutes?

- … that the 1988 Winter Olympics saw the first appearance of a Jamaican team at a Winter Olympics, and would go on to inspire the film Cool Runnings?

- … that a spectator who threw a bottle at the men’s 100 meter race in the 2012 Olympics was immediately confronted by judo bronze medalist Edith Bosch, who happened to be next to him? The chairman in charge of organizing the games later said that “I’m not suggesting vigilantism but it was actually poetic justice that they happened to be sitting next to a judo player.”

Aubrie Johnson, Social Media Associate

Wikimedia Foundation

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation