The National Library of Wales has been sharing images openly on Wikimedia Commons for about two years, through its own Wikipedian in residence, so that they can be added to Wikipedia articles and freely reused by everyone for any purpose.

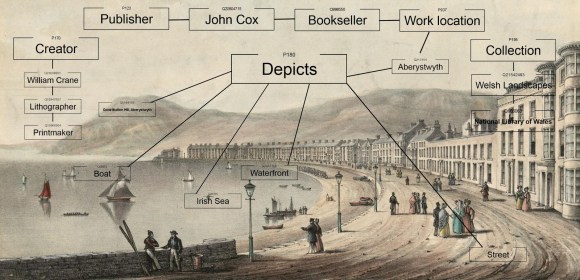

Along the way, the library realised they had a large amount of cataloguing data for some of the collections they were sharing. This metadata was not easily accessible and couldn’t be explored or visualised in any meaningful way. They decided to port all the information they had about their collection of Welsh Landscape prints into Wikidata—free, open, linked data which anyone can access, interpret and visualise.

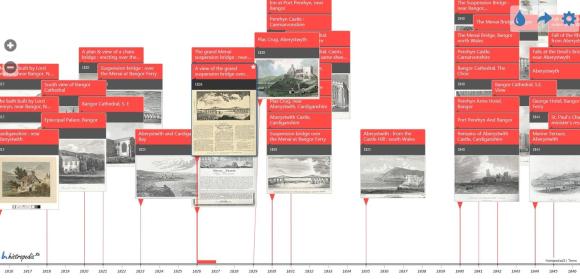

From 1750 to 1850, Wales gained popularity as a destination for visiting artists like J M W Turner, thanks in part to prior efforts by painter Richard Wilson, a prominent figure in the early history of British landscape painting who drew attention to the scenery of his native country. The simultaneous rise of the print industry meant that these works of art were reproduced using an array of different printmaking techniques for the first time. The result is a fantastic collection of views that includes towns, castles, rivers, waterfalls, mountains, lakes, country houses, churches, cathedrals and many other interesting features of the Welsh landscape and a chronological record of the developments in printmaking.

The world’s first Wikidata Visiting Scholar

This project presented a unique opportunity to create detailed linked data for an entire collection, complete with openly licensed images and data about each artist and engraver, along with the places, people and things the images depict.

In order to achieve this goal, the National Library of Wales handed their data over to Cobb, the Visiting Scholar, who began the task of converting it into items, properties and qualifiers.

Cobb needed to create Wikidata items for each of the 4,650 images in the collection, match up each of the collection’s 586 artists and engravers with existing data, and create new entries for artists who were not yet recorded in Wikidata. He would also need to convert 1480 different descriptive tags into Wikidata items.

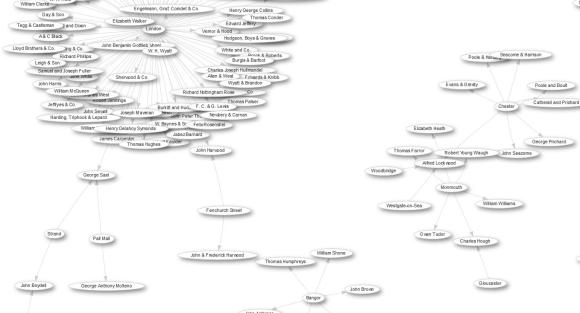

To do this, Cobb had to research many of the artists and publishers in order to create the data, and in many cases he was able to link the Wikidata item to the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF). Authority control ensures that works by a particular creator are entered under a uniform heading and that each heading is unique, which is important to prevent works by more than one creator being entered under a heading. Creating a link between Wikidata and other authority records also help connect data sets together, making it easier to discover, add and improve Data in the future

The power of linked data

Despite the scale of the task at hand Simon has now completed his exciting challenge and the results are fascinating. When asked about the power of this linked data Simon said:

Obviously I’m delighted that it is now possible to plot the locations depicted in the Welsh Landscape Collection on a map, browse the prints in a variety of ways, including by subject, county or artist, and visualise the quantitative aspects of the Collection, such as the number of works by an artist or places most frequently depicted. However, it is important not to overlook some of the more mundane uses of the Wikidata, like the ability to generate lists that can be sorted by particular properties.

First, the artwork and metadata that comes with it are available to all, and it is hoped that this will encourage innovative reuse, visualisation, and interpretation, as has been demonstrated by the work of other ‘open’ cultural institutions like the Rijksmuseum and by the British Libraries BL Labs initiative.

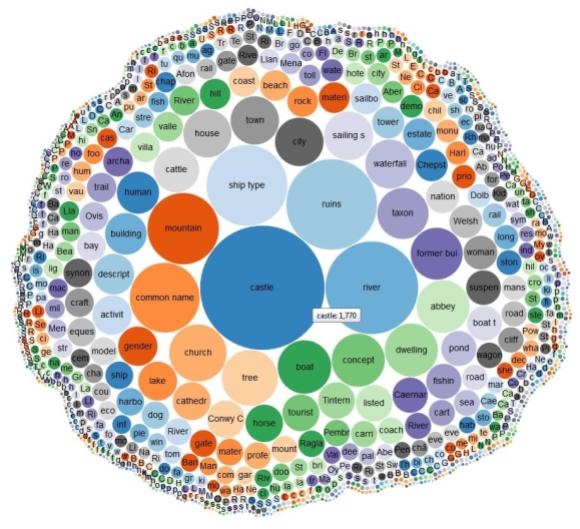

Second, it is now possible to easily analyse the data in ways that was not possible before. For example, we now know that castles are by far the most frequently depicted subject in the collection, followed at a distance by rivers and ruins. Conwy Castle is depicted more than any other. Also to be found are 158 images people fishing, 101 images of sheep, and two images of fox hunting.

As each item is comprised of statements that describe the entity’s properties, we can run queries that would not have previously been possible. This opens up answers to questions ranging from birthplaces of the artists and images created by members of the clergy, to tracing the development of the print trade in Wales and beyond.

The vast majority of the artists and publishers responsible for the prints in the collection have been identified and linked to a Wikidata item. This has revealed that the prints were produced by 489 engravers, after the work of 217 artists, and were issued by 362 publishers. Although there are 52 different places of publication, 32 of which are in Wales, more than half of the prints (2,562 prints) were published in London, with Chester (124 prints) and Bangor (96 prints) being the most frequent provincial and Welsh publishing location, respectively.

New tools are being developed for visualising data, which are increasingly sophisticated and more user-friendly. Many of these tools are free to use and can be used to discover cultural data in new ways. Histropedia, for instance, has been developing a timeline tool which uses Wikidata. Here, the Welsh Landscape Collection is organised chronologically on a timeline.

What’s next?

The National Library of Wales is excited about the opportunities for collaboration and creative re-use that comes from sharing such rich data without restrictions, and is looking into holding a hackathon in the near future in order to encourage reuse of Library content on Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons.

Simon is keen to continue working with the National Library as a Wikidata Visiting Scholar, and the Library is looking forward to supporting him in his work by providing access to its cultural data.

Jason Evans, Wikimedian in residence

Simon Cobb, Wikidata Visiting Scholar

National Library of Wales

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation