Suppose a consumer named Alice buys a record of a David Bowie music album. Although Alice is not an expert in property law, she probably knows what privileges she enjoys by buying the LP record. For example, Alice can freely lend or rent it to her friend. Alice also possesses similar rights if she were to buy a book. But what happens when Alice buys an e-book or a song on iTunes? Can she enjoy the same rights with the e-book as she could with the book? Can she lend it or rent it to whoever she wants without any restrictions? Probably not. In the online world, users’ rights on digital copies and content are subject to licensing and technological restrictions imposed by copyright holders.

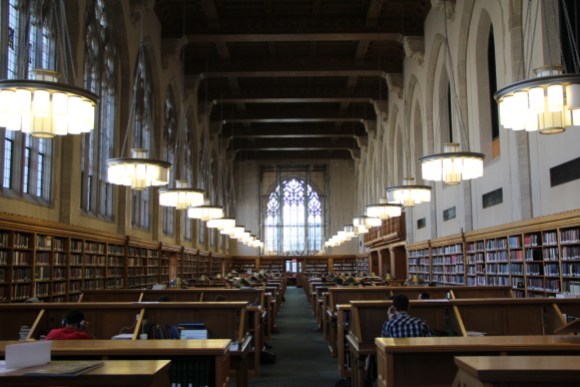

How we approach content licensing is critical for the Wikimedia projects and our mission of spreading free knowledge around the world. To help us better understand current research on this issue, I recently attended a talk on this subject hosted by our friends and collaborators at the Yale Information Society Project. The talk, entitled The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy, was given on November 3, 2016 by Professor Aaron Perzanowski of Case Western Reserve University.

Intellectual property, including copyright, is governed by the principle of exhaustion, also called the first-sale doctrine. This principle, established in Bobbs-Merrill Co. v. Straus in 1908, holds that copyright holders lose their ability to control further sales over their copyrighted works once they transfer the works to new owners. Bobbs-Merrill, the plaintiff and a publisher, drafted a notice in its books forbidding sales under one dollar, warning that violations of this condition would be considered copyright infringement. The defendants resold the books for less than a dollar each. In the end, the United States Supreme Court agreed with the defendants’ position and sent a clear message that copyright holders are not able to control prices or resales after the first sale of the copyrighted work. Even today, the first-sale doctrine is an important defense for consumers. In Alice’s case, copyright holders can control any use of the physical copy of the Bowie LP record until the first sale to Alice. Once Alice owns the record, she can re-sell it, donate it, etc.

But according to Perzanowski, the notion of property has changed: in the past, copies used to be valuable because they were scarce and difficult to produce. In the internet era, the paradigm has shifted. Because everything disseminates quickly and at almost no cost, copies have lost value. This is why buying in the digital world is a different experience. If Alice wants to buy an e-book on Amazon or an album on iTunes, she is not actually buying the “copy” of such e-book or album, but instead is licensing them. According to Perzanowski, these licensing schemes are undermining consumers’ rights that once were protected by ownership. Generally, the license terms of digital products will include the prohibition against transfer and sublicensing, among other restrictions. Thus, the notion of a copy of a work is disappearing, because in these licensing schemes, rights that are obvious in a physical object like resale, rental, or donation rights are neglected. Furthermore, these restrictions are authorized by law, specifically the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which includes provisions on Digital Rights Management (DRM) technologies that limits the consumer’s ability to use the product. If Alice buys an e-book, DRM technologies and legal provisions may limit her ability to print and copy-paste, and may impose time-limited access to her book.

Unfortunately, consumers do not seem to understand these limitations of the digital market. Perzanowski explained that 48% of online consumers think once they purchased an e-book by clicking on the “buy now” button, they are able to lend it to someone else and 86% think they actually own the book and can use it in the device of their choice. Perzanowski believes that consumers should be better informed so that they can have a better sense of autonomy on how to use the digital products they buy. For this reason, he advocates for better education on digital licensing so that consumers can recalibrate their expectations.

The use of Creative Commons (“CC”) licensing for content on the Wikimedia projects helps address Perzanowski’s concerns regarding limited consumer rights with respect to digital works and consumer education on digital licensing. First, CC licensing allows the Wikimedia communities to enjoy broader rights for digital works, such as the ability to share content with a friend or to produce derivatives, that are not available under more typical digital licensing schemes. Second, Creative Commons’ and the Foundation’s approaches to licensing provide certainty to consumers and promote transparency in how they can license content. For example, Creative Commons provides summaries of CC licenses in plain English. Similarly, the Wikimedia Foundation clearly explains to its users and contributors their rights and responsibilities in the use of CC licensed Wikimedia content. The Foundation also publicly consults with the Wikimedia communities on these licensing terms; it recently closed a consultation with the communities on a proposed change from CC BY-SA 3.0 to CC BY-SA 4.0.

In today’s world, physical copies and analog services are more the exception than the rule. This, however, shouldn’t mean that digital copies and online services have to be offered with fewer rights for users compared to rights available under traditional licensing schemes. We support licensing schemes that allow users to retain the same rights that they would otherwise have in the offline world so that users have the power to edit, share, and remix content: the more we empower, the more knowledge expands and creativity grows.

We believe strongly in a world where knowledge can be freely shared. Our visits to Yale ISP allow us to remain engaged in discussions about internet-related laws and affirm the importance of licenses like Creative Commons for the future of digital rights.

Ana Maria Acosta, Legal Fellow

Wikimedia Foundation

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation