Eddie Chapman’s codename in the British Secret Service was “Zigzag”—appropriate for a World War II double-agent. The Germans called him Fritz, or the affectionate diminutive, Fritzchen. (The Germans liked him.)

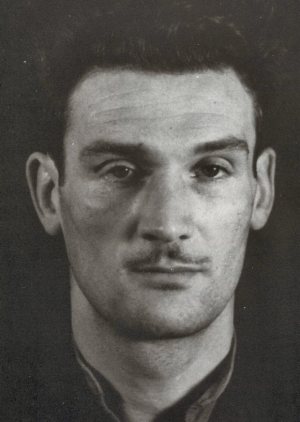

With handsome, off-kilter features and a pencil-thin mustache, Eddie Chapman looked like a dinged-up Errol Flynn. He even worked for a bit as a film extra. Eddie did all kinds of things.

He joined the British Army at 17, ran off with a girl, got arrested, tended bar, gambled away all his money, and became a safecracker with London’s “Jelly Gang.”

Just after his time with the Jellies, Eddie made a daring escape reminiscent of movie star Errol Flynn as Robin Hood or Captain Blood. According to the Wikipedia article on Eddie:

| “ | Chapman had been dining with his lover and future fiancée Betty Farmer at the Hotel de la Plage immediately before his arrest and, when he saw undercover police coming to arrest him for crimes on the mainland, made a spectacular exit through the dining room window (which was shut at the time). | ” |

While in prison for theft, Eddie “confirmed his willingness to act as a German spy. Under the direction of Captain Stephan von Gröning,” the article says. He was “trained in explosives, radio communications, parachute-jumping and other subjects.”

Loyalty was never Eddie’s strong suit, and he soon offered his services to his home country, which also took him up on it.

And here one finds a significantly redemptive pillar of Eddie’s life. According to the Wikipedia article’s source Zigzag: The Incredible Wartime Exploits of Double Agent Eddie Chapman, by Nicholas Booth, Eddie may have saved central London from heavy bombing. He consistently gave the Germans misinformation about their bombing targets, and as a result many bombs missed those heavily populated areas by a good deal, landing instead in the suburbs of Kent.

But don’t afix a halo too securely to Eddie’s head. During this time he was also fixing dog racing bets by drugging greyhounds at a track.

A double agent of love, or at least betrothal, Eddie had two fiancées in two warzones at the same time: Freda Stevenson in Britain, and Dagmar Lahlum in Norway. The only equitable thing was to abandon them both, which Eddie did.

He married a third fiancée, Betty Farmer (his date for the daring restaurant escape), and they stayed married for 59 years until Eddie’s death in 1997. Perhaps the most amazing part of Eddie’s life is his marriage’s patient endurance.

After the war, a movie on Eddie’s life was made in 1966, with Christopher Plummer in the starring role. “In his autobiography, Plummer said that Chapman was to have been a technical adviser on the film,” the Wikipedia article says. “But the French authorities would not allow him in the country because he was still wanted over an alleged plot to kidnap the Sultan of Morocco.” In some lives this accusation would be scandalous, but it dangles prosaic in Eddie’s story like a delinquent parking ticket.

After all the swashbuckling espionage and misadventures, Eddie left something behind. Or someone. And she matched Eddie’s rakish disloyalty with humbling devotion.

Unlike Eddie, Dagmar Lahlum—his Norway fiancée—was an incredibly loyal and covert spy. They met during the war at a bar in Norway where she was “smoking Craven A’s with an ivory mouthpiece,” the Wikipedia article on her says. She thought he was German; he thought she was a prostitute. Later they discovered they were both spies for the same side. They lived together in Oslo while they worked gathering intelligence against the Germans. They talked of getting married, opening a restaurant, and having children.

Eddie zigged and zagged, went back to Betty, and had a movie made about his life. Dagmar never revealed her life as a spy. She served a six-month prison sentence for supposed treason in Norway, and was shunned as a German collaborator. “Many years after the war, her neighbours would still whisper darkly that she was a German whore,” her Wikipedia article says.

Decades after her death, a niece found a box of letters in Dagmar’s home. One by one the niece read the letters and was astonished. Into view came a film noir story, out of the blank past, as if written in disappearing ink.

A woman in a nightclub smokes with a cigarette holder. A rakish man in a German uniform looks her in the eye. In a private room they discover they are allies. For a while they live their double lives together, dancers trailed by their matching shadows.

None of the letters, written over years, had been sent. All of them were addressed to Eddie.

Jeff Elder, Digital Communications Manager

Wikimedia Foundation

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation