Every December, the Foundation’s online fundraising team conducts our most wide-reaching donor drive of the year, known internally as the Big English campaign. Coinciding with the end of the calendar year, considered the highest-value time period for charitable giving in the Western world, we present fundraising appeals on Wikipedia to readers in some of our largest English-speaking countries.

The Big English campaign is seen by millions of Wikipedia users, giving us an unparalleled opportunity to raise much needed revenue while educating readers about our non-profit status. But striking the right balance between education, persuasion, and saturation is a constant challenge.

Until December 2016, we throttled our fundraising banners on Wikipedia in two stages. For the first two weeks of a campaign, we would not cap the number of impressions shown to users. This meant that every reader would see a banner on every page visit to Wikipedia. After the two-week mark, we capped impressions at a maximum of 10 per device, having learned that the efficacy of our appeals consistently dropped over the course of a fundraising campaign.

Still, we didn’t have the hard data to determine exactly where our most effective impression cut-off was. Our compromise of 2 weeks at 100% effectively penalized power users of the site; for daily readers, every visit and every clickthrough meant another banner.

We are keenly attentive to any sign that our fundraising appeals are hurting traffic to the site. We know, from thousands of survey responses, that most Wikipedia readers don’t consider our fundraising content too intrusive or aggressive. But we also knew there had to be a better way to determine when to limit banners so that readers had a fair chance to contribute without experiencing burnout. And last December we found one.

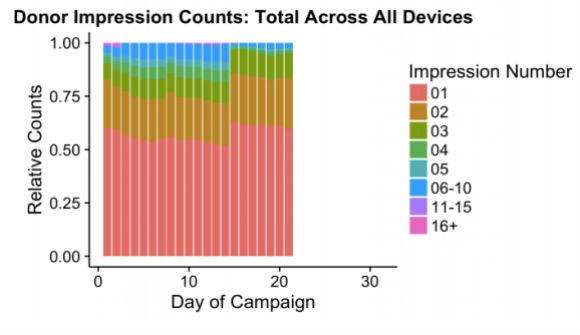

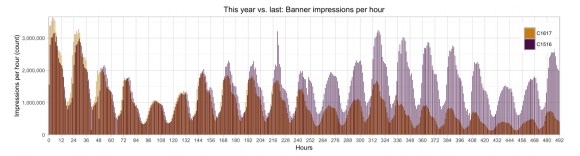

Top: Donor impression counts in 2016. Bottom: Banner impressions per hour, 2015 vs. 2016. Graphs by the Wikimedia Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0.

We crunched the data on last year’s banner impressions to determine which ones generated the largest number of donors (‘donor conversion’). Looking at the distribution across all devices, including mobile, tablet, and desktop/laptop computers, it became apparent that the first handful of banner impressions is where we converted the vast majority of donors, and the decline in conversion afterwards was undeniable.

Each subsequent banner impression after the first exhibits a rapid dropoff in conversion. After the tenth, the conversion rate is minuscule: only about 3–5% of donors donate after the 10th impression. With the data in hand, there was no need for debate; we would gladly trade that lost revenue to know that we aren’t burning out readers with ineffective and relentless fundraising messages.

What’s more, we validated a central premise of our fundraising strategies: that our model depends upon a wide readership contributing small amounts of money to sustain Wikipedia and its related services. It would be both annoying and ineffective to run fundraising banners on Wikipedia constantly throughout the year. Our strategy of annual high traffic campaigns in a rotating lineup of countries ensures that our content stays fresh and engaging to readers, while offering readers around the world the opportunity to become a sustaining donor of the world’s independent encyclopedia.

Although we’ve reduced banner frequency, we’ve still been able to match or exceed revenue in our fundraising campaigns, compared to previous years. There is always room to improve our approach to fundraising. If you have a suggestion, please share it with us at fr-creative[at]wikimedia[dot]org.

Sam Patton, Senior Fundraising Campaign Manager, Online Fundraising

Wikimedia Foundation

Want to work on cool projects like this? See our current openings.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation