Few websites are as massively multilingual as Wikipedia. An article on Wikipedia may be available in several languages—and readers and editors may want to view that article in a language other than the one their browser automatically selects.

This creates some challenges for the Wikimedia Foundation’s Language team, which formed in 2011. We want to make sure that both readers and editors can always select the language they want—and just released a new feature to English Wikipedia that will make the language selection process easier.

In this post, I explain the history of interlanguage links on Wikipedia and detail how other organizations approach multilingual readers. But first, let’s look at why people may want to read an article in a particular language.

Serving multilingual readers

On Wikipedia, millions of articles are available in more than one language. Many are available in more than a hundred languages. For example, you can read the article about the jazz musician Louis Armstrong in 120 languages, the article about the Indonesian singer Anggun in 141, and the article about Beijing, the capital of China, in 218.

People have different reasons for wanting to read an article in a particular language. Most readers simply want to read an article in the language that they know best, but even that is often a challenge: many people search for the topic that interests them on a search engine, and then wind up on Wikipedia through their research results. But the search engine doesn’t necessarily bring them to the article in the language that they want.

At that point, if an article is available in their language, they may click on their language name in the sidebar. But what if the article is available in fifty languages? As our research has shown, finding their language name in such a long list is difficult, and many people are not even aware that a Wikipedia in their language exists.

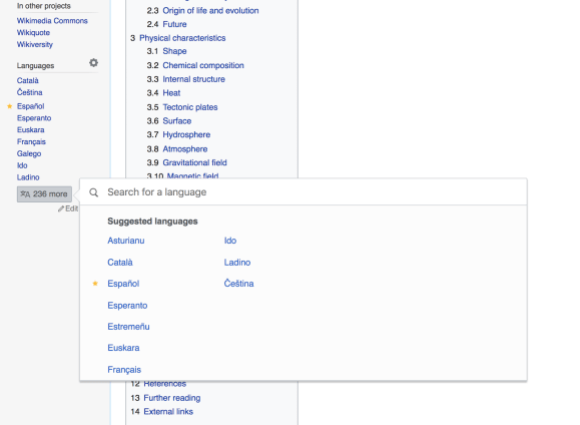

It could be quite a long list (left sidebar). GIF from the English Wikipedia’s article on Earth, text available under CC BY-SA 3.0.

How different websites resolve this problem

There are different methods for showcasing language availability. As part of our research we explored existing approaches.

When a website is available in a just a handful of languages, it is convenient to simply show a list of these languages’ names. But when the number of languages increases, using a plain list becomes problematic. Listing also requires you to think about ordering languages.: For example, where will Japanese appear—at “J”, according to its English name, between Italian and Korean? At “N” by its native name “Nihongo”? Or perhaps towards of the list, because its own name is not written in the Latin alphabet?

In some websites and apps, the names of the languages are all written in the same language, and they are sorted alphabetically. For example, common machine translation websites work like that. This may seem convenient, but in fact, finding a language in a list of more than twenty items takes quite a few seconds, despite the alphabetical sorting. And if the computer is set to work in Hebrew, and it is used by somebody who knows only English, it will be very difficult to set English as the target language for translation if “English” is written as “אנגלית”.

Clearly, when the user can select from so many languages, there are many possible solutions. So how did we approach this challenge?

Sorting doesn’t come overnight

Wikimedia’s Language team has been working on this language sorting and selection problem since 2012 when we designed and released the first version of the Universal Language Selector extension (ULS). The ULS was initially made not as a way to move between versions of an article, but as a generic design for making it easy to select a language from a long list of languages in various contexts. Its first use was setting user preferences related to language.

The design included dividing the complete list of languages by continents on which they are spoken, and then further dividing them by writing system, and sorting alphabetically within the writing system. Another section was added at the top, with the languages that are most likely to be known to the reader: the languages on which they previously clicked, the language of their operating system and browser, and the languages of their country.

The panel also showed a search box, which allows users to find the language they need as quickly as possible, and in any language. So even if you don’t know Japanese and cannot type in it on your computer keyboard, you can type “Japanese” in English or “Ιαπωνικά” in Greek and find “日本語”.

ULS was soon adopted for use at Wikidata, the Translate and Content Translation extensions, the Upload Wizard and in other locations in Wikimedia sites. However, the ULS didn’t tackle what may be the most visible and challenging context for language selection: moving to a version of the article that you’re reading in another language.

The only significant attempt to change the design of interlanguage links was made in 2010, when the list of languages was made completely hidden by default in an attempt to reduce visual clutter. The complete hiding of the links caused the number of clicks to drop by about 75%, and after several weeks this change was reverted.

The new compact language links.

This problem began to be addressed again in 2014, when Niharika Kohli, who is now a software engineer at the Wikimedia Foundation, adapted ULS to interlanguage links as part of her project with OPW, a program now known as Outreachy. This feature compacted the complete list of languages in which a page is available to at most nine items. This number was chosen according to a common guideline in design and psychology: The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two, the number of objects an average human can hold in working memory. The rest of the languages are shown using a “More” button, which would show a ULS panel with all the languages in which the article is available.

The languages for the initial nine-item list were chosen according to the same criteria as the languages for the top section in the ULS panel. The highest priority is given to the languages that the user had clicked previously. This helps users avoid scanning the list again and again for their usual languages. This optimizes for repeated use which has a larger impact on regular use of the site. In addition to previously-clicked languages, languages are added according to user’s operating system settings and the language’s spoken in the country from which the user is connecting.

This feature was enabled as a beta feature in 2014, and the team started collecting feedback from the editors who enabled it.

A common theme in the feedback was the need to adapt the feature for Wikipedia editors, whose needs are different from those of casual readers. While casual readers usually want to read the article in a language that they know best, people may also want to read an article in a different language for other reasons. For example the article in their language may be too short and they want to try to read in another language to learn more. Wikipedia editors may also want to look at the article in the language that is related to the article’s topic. For example, they may want to look at an article about a city in Tunisia in the Arabic Wikipedia even if they don’t know Arabic. This is useful for finding more images, comparing the article’s length and structure, finding the native spelling of names, and so on. They may also want to find in which languages does that article have the “featured article” status.

Based on this feedback, the feature was modified to prioritize languages for a user’s initial list based on several more criteria: languages from the user’s Babel userboxes, which many Wikipedia editors use to tell the world about the languages they know; languages in which the article is featured; and languages that are used in the article’s text. It also started indicating languages in which the article is featured with an appropriate icon (usually a star). Many visual tweaks were also made: for example, the division into sections by continent was removed when it’s not needed—when the list is too short for the sections to be useful, or when the panel is showing search results.

How language links will look now, on desktops. GIF from the English Wikipedia’s article on John Maynard Keynes, text available under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Some Wikipedia editors also improved the database of languages by territory, which is maintained as part of the CLDR project. This improves the relevance of languages that are shown in the initial compact list according to geolocation, and it is also a fine example of how Wikipedians collaborate with other open data projects.

In June 2016, the team has begun gradually moving Compact Language Links out of beta status in different projects. Showing a compact language list had notable impact: after one year, the percent of users who click the interlanguage links almost doubled across all languages. Traffic through interlanguage links into all languages has grown, and this includes languages that are smaller and aren’t tied to any country, such as Esperanto.

By February 2018, the English Wikipedia became the last Wikipedia in which the feature was taken out of beta. The English Wikipedia is the most read Wikimedia project, it is read by at least some people in all countries, and it acts as a gateway for Wikipedia in many other languages, so it’s particularly important that interlanguage links in it are as optimized as possible for the global audience.

What does the future hold for the interlanguage links design? There are no solid plans to change anything at the moment, but it’s pretty clear that Compact Language Links is only the first step in the redesign of the interlanguage links. Future changes may include:

- Showing links to all the languages, rather than just the languages in which the article is available. Actual implementation of this will require proper research and design, but this is supposed to let the users know that there is a Wikipedia in their language; currently, languages with fewer articles have a lower chance of showing up in the interlanguage links list. Links to languages in which the article is not available can lead the user to a list of basic facts using Article Placeholder or Wikidata, or to creating a translated article using Content Translation.

- Showing the list of interlanguage links in a more prominent location on the page.

- Redesigning the different elements near the language list: the gear icon for language settings, the “more” button, and Wikidata’s “Edit links” element.

- Making the algorithm for prioritizing the languages common for the desktop site, the mobile site, and the mobile apps.

Wikipedia is already one of the web’s most linguistically diverse sites, and better design for its languages list may uncover an even bigger potential for language diversity.

Amir Aharoni, Product Analyst, Language team (Editing)

Wikimedia Foundation

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation