If you haven’t already read it yet, this is the second in a series of three blog posts about the creation of lists in the Wikimedia Movement. Check out part one “Lists in the Wikimedia movement? Why? What?“

In the last post, I described why communities create lists, and with the next three posts I am going to describe what kinds of lists are common amongst Wikimedia communities so that you can choose which tactic to use to make your own.

Wikis have driven the self-documenting practices of many parts of the internet: knowledge management for pop culture, businesses, and software developers, among many others. At its core Wiki software is effective at taking the kinds of tasks that one might make in a private notes document or offline note taking environment, and make them easy and straightforward for the collaborative internet. One of these practices is list building, so the wiki software has some basic functionality that meets this need.

Most people start their list-building practices in the Wikimedia community with the simplest manual forms of lists. For this post, I dug into my own experience in the movement: list building was at the core of my volunteer editing on English Wikipedia. English Wikipedia is a relatively special space for list building: because of the size, experience and complexity of the editing community, the options for creating lists are wide and varied. I expect that English Wikipedia is a bit different than many smaller wikis or non-Wikipedia wikis.

In this blog post, I am going to focus on two “genres” of list-building that happen organically on wikis: Manual lists in collaborative spaces, and creating lists by leveraging navigational tools within the content on Wikimedia projects. Let’s learn more about it!

Manually creating a collaborative list

On Wikipedia and other Wikimedia projects, manual lists have historically been the life blood of different kinds of contests, drives and topical workflows. Generally these lists come in two different flavours: Red link lists are lists of articles to be created (these red link lists are the namesake of WikiProject Women in Red); and Blue link lists: content that already exists on the Wikimedia projects but could be improved. Most communities use a mix of both types of lists to keep track of potential new and existing content to improve and maintain that content.

On Wikipedia, the most useful manual lists for sharing with other editors include references and descriptions of the content that is missing — a simple “red link” without context doesn’t help contributors understand the intended topic’s scope; and new editors, with less research experience, or experienced editors that are feeling particularly lazy (or rushed #100Wikidays victims), can easily jump into writing the topic without much research time. At a recent Amnesty International editathon in the Netherlands, they distributed this topic list in an analog way with sticky notes and folders of printed research.

The ease of creating a manual list is also closely attached to its major flaws: first, manual lists are often associated with a single event or activity and get lost in the sands of time (we are still missing WWI dissenters identified for an editathon I supported in 2014 for example). If my experience mirrors that of others in the movement, there are dozens of “opportunities” for topics I have identified with experts or partners that will never be acted on.

Moreover, without a clear community ready to receive that list (like a WikiProject like Women in Red), it’s not a simple task to focus folks on addressing those gaps. For example, the topic gap opportunities identified as part of a Gap Finding Protocol experiment in 2016 — how do we know that expert feedback was integrated, without extensive manual research into the history of individual pages on English Wikipedia?

Even when the community is ready to receive a manual list, managing and cleaning the list of completed tasks becomes daunting, distracting some of the more experienced and skilled contributors to the Wikis. Take, for example, WikiProject Missing Encyclopedia Articles on English Wikipedia, where a significant amount of labor has been required to maintain the lists — and many of those lists are not up to date. Similarly, the manual lists from WikiProject Women in Red have to be regularly cleaned by the more experienced editors in the project.

Also, as the Wikimedia community operates in more and more multilingual environments, sharing these manual lists across Wikis is nearly impossible: a manual list does little good for soliciting international attention and collaboration. Especially in a time when translation could be a simple and easy way to engage multilingual newcomers across many communities, sharing a manually created listed is cumbersome.

Strengthening an on-wiki category, list or template

A slightly more robust and persistent way of gathering content on Wikimedia projects is integrating manual lists into the content on the projects themselves through list articles and navigational tools, like categories and templates, that both help folks navigate between articles and identify missing topics.

For example, when I was writing new articles about fiction for #100WikiDays, I would use awards lists, publisher list articles (like the Heinemann African Writers Series), and author navigation templates (i.e. James Fenimore Cooper). Whenever I am looking for a straightforward, probably notable topic — these kinds of lists are a great way to start because they typically mean another editor, in creating the list, thinks there is a high probability of notability.

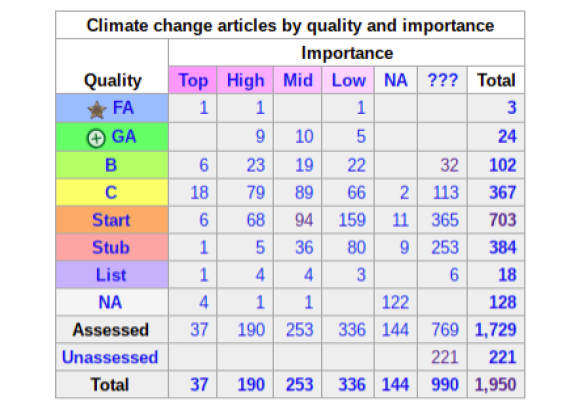

On some of the larger Wikis, the WikiProject and its associated article assessment tools can be a good place to start for already created content (i.e. the Wikipedia 1.0 tables and WikiProject categories embedded in templates). On English Wikipedia, an ecosystem of tools has evolved around monitoring and focusing attention on these articles. For instance, if you want to work on one of the backlogs tagged with backlog templates, you can use the CleanUpWorkListBot Tables to monitor the backlogs for each WikiProject and solve them on your own.

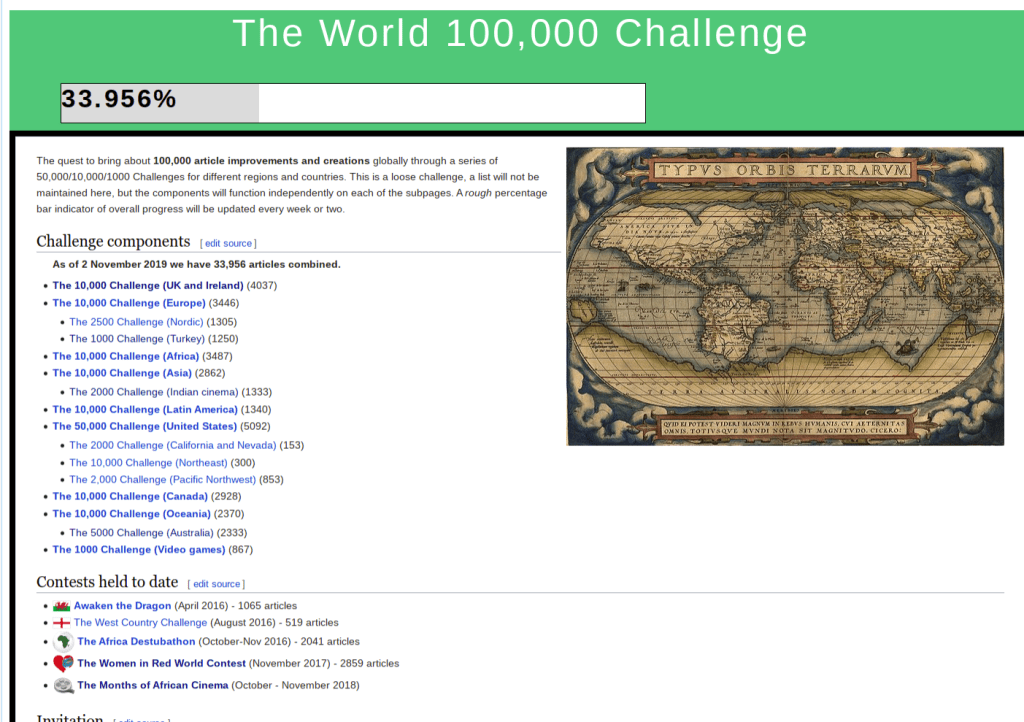

Moreover, some Wikimedia projects have well maintained category systems that can be used to suggest a topical area to work. For example, on English Wikipedia the stub tags and categories are actively “sorted” into smaller more actionable sets of topics where, theoretically, folks can find a stub to expand. However, those categories have been continuously growing in size and complexity since I started editing on English Wikipedia, making them quite overwhelming in my experience. The only meaningful “de-stubbing” I have seen of this content has been during the sub-campaigns within the 100,000 Article Challenges User:Dr. Blofeld initiated several years ago.

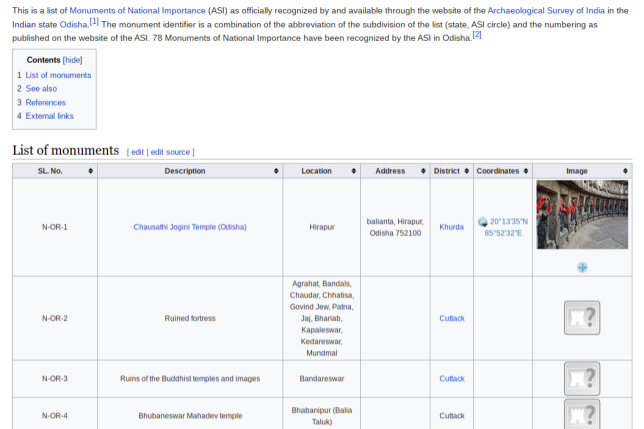

For many years, the core component of the Wiki Loves Monuments lists were on-wiki tables generated by a mix of manual human intervention and bot tools (i.e. the List of Monuments of National Importance in Odisha). These lists maintained on the Wiki provide redlinks, links to upload pictures to Commons, and useful information for casual browsers on Wikipedia, but required an overwhelmingly complex system of technology to make them work.

These kinds of list making approaches all have limits similar to the ones described above for purely manual todo-focused lists: they are not multilingual and they can easily get lost in onwiki processes (for example, in my experience categories on Commons and English Wikipedia can change rapidly based on the whims of editors and the trending information hierarchy). Moreover, beyond not being multilingual, maintaining these complex template, category, and WikiProject structures on our wiki platforms requires a lot of labor and complex skills. Smaller language Wikipedias typically don’t have the level of complexity required to create most of this kind of content.

Moreover, on English Wikipedia, and I am imagining other more mature Wikipedias, leaving red links on such lists is not very popular and some editors favor quick and easy solutions to not covering a topic (i.e. a redirect to another more general article). And if your goal is to help new contributors identify topics, these navigation tools turned topical lists can be cryptic: which is a good article to start with? What do the various subcategories contain in relationship to the larger topic? What if I don’t find sources for that redlink, do I remove it? In my mind, these in-content navigation tools are really only there for the experienced contributor.

What’s next?

If the manual list or leveraging the navigational and organizational tools on the wiki isn’t enough: what then? Wikidata has unlocked a number of new and interesting ways for generating lists in the Wikimedia-verse: the next post in the series will discuss that.

Lists in the Wikimedia movement Part 3: The List Revolution: Creating dynamic lists using linked data

Like this blog series on lists? We need your help documenting list building practices and imagining new and more powerful ways to leverage the list building practices we have so far in the community: how would you make the lists more portable? What kinds of lists or data would you like to collect? If you do something I haven’t covered yet, let me know by reaching out directly via astinson@wikimedia.org, leaving a comment on this post, or sharing the examples on the talk page of the Organizer Framework for Running Campaigns.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation