The Foundation 360 series profiles important work happening at the Wikimedia Foundation, and the people behind it.

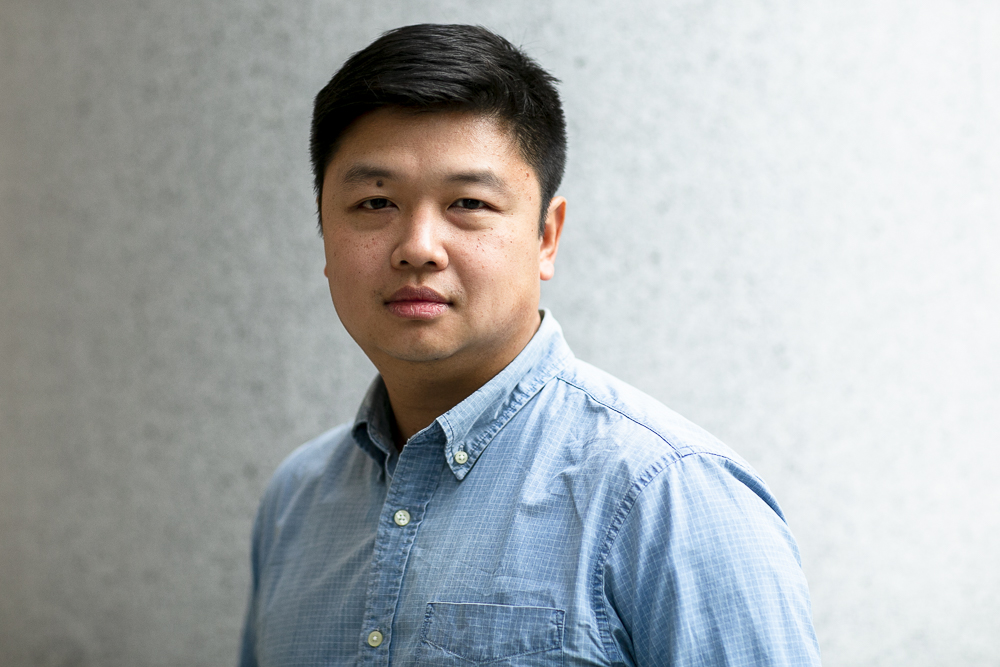

Whether he’s sitting in a broadcasted government hearing or speaking on an after-hours video call, Sherwin Siy, Lead Public Policy Manager for the Legal Department, lights up when he talks about supporting digital rights policy for the Wikimedia Foundation. “The reason I went to law school in 2002 was because I was inspired by the ability for the internet to be this collaborative, weird place, built out of collections of individuals,” he told us.

Deeply inspired by the weirdness of the internet and seeking to protect it, Sherwin made it his mission to support “the unanticipated things that are made by people who aren’t multibillion dollar corporations.” That’s where Wikimedia comes in: “Wikimedia projects are one of the biggest and most prominent living representations of that spirit. That’s why I’m working here.”

We talked with Sherwin about the work of the Public Policy team over the last year to protect free knowledge online and, with it, Wikimedia contributors’ ability to keep doing the work they do on the projects every day.*

Q: I’d like to get a sense of what your team is like. If you had to compare the Public Policy team to a character in a novel, what would you compare it to?

SS: We would be an Ent from Lord of the Rings. We support the hobbits that are on a mission. The hobbits have a thing that they know needs to happen and they come to the Ents and they tell them their problem. Then the Ents have a weeks-long conversation in incomprehensible language over what to do next. And for them that’s a fast conversation. There are these intertwined elements that you need to bring to bear on an issue and we need to come to an agreement before we strike out with a statement or comment or another type of forceful action.

A lot of the work we do is invisible, but it is critical to being as effective as possible in advocating for Wikimedia projects. Underneath each action we take is a constant amount of work for us to try and explain what Wikimedia projects are to policymakers in language that they understand. To box out a space for our movement in these incredibly contentious debates about content moderation, about copyright and about protected forms of speech, among other things.

Q: The Public Policy team has been involved in a number of actions throughout the year. Can you tell us about some of the most impactful ones?

SS: Over the past year, we’ve been involved in more than 30 policy actions around the world on topics that directly affect Wikimedia editing communities. The actions ranged from government briefings, panel discussions, blog posts, responses to government complaints, official memos, open letters, and lots more.

Two of the topics we worked on in depth this year were “notice and staydown” systems and content moderation. Members of the Public Policy team gave live testimony at some high-profile events on these topics, including a US Senate hearing, a Mexican Senate briefing, and a hearing at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Q: What is a “notice and staydown” system? Why should Wikimedia contributors care?

SS: Often it’s not well-defined, even in legislative proposals, but generally, a “notice and staydown” system goes farther than a “notice and takedown system,” and governments in multiple countries are considering incorporating it into copyright legislation. Rightsholders are lobbying governments to be able to send platforms a URL of copyright infringing material, and have the platform immediately take it down and keep it down. This would seem to mean that platforms would have to devise a way to recognize that file anytime it’s introduced in the future and either prevent the upload or automatically take it down again.

Any system that would interact with uploads in that way would pose a threat to fair use. That’s because with fair use, context matters. Fair use allows for portions of a copyrighted work to be copied or incorporated into another work so long as that use is considered “fair.” Uses like parody, reporting, teaching and research fall into this category. Fair use is what allows Wikimedia editors to confidently add a lot of images, sounds, music, quoted text, and video to the projects when no freely licensed content is available. A “notice and staydown” system could mean that any time an editor attempts to upload any part of a previously identified copyrighted work, that upload could be blocked or automatically removed, even when its use on the projects is completely legitimate. This could have dramatic negative consequences for editors that contribute multimedia and editors that use it to enrich text content. Of course, it could also have negative implications on the availability of multimedia in the free knowledge ecosystem more generally. Photos, videos, illustrations, and things like this are critical for both creating knowledge and relaying knowledge, and without freedoms around their use, our ability to live up to our mission would be seriously compromised.

So we were there to speak before the US and Mexican Senates about these things, to explain why a “notice and staydown” system would pose a serious threat to Wikimedia projects and other similar projects.

Q: Can you tell us about the work you did this year on content moderation? Why should content moderation legislation matter to Wikimedia contributors?

SS: Content moderation isn’t just about ‘Are you leaving up or taking down copyright infringement?’ or ‘Are you leaving up or taking down abusive material?’ Content moderation is how you shape what a website or project is. It’s how you make Wikipedia Wikipedia, and not a listing of every videogame guide that ever was. Content moderation makes the identity of the project or platform. It’s not just removing bad stuff, it’s removing irrelevant stuff.

Content moderation is what the communities do on Wikimedia projects. Most governments don’t understand how the projects work, and that communities, not the Foundation, are the ones doing the content moderation. The questions that governments are asking themselves is ‘What content should we allow and what content should we prohibit?’ and that’s how they think of content moderation. They often don’t realize the fine grained content moderation policies and details that a Wikipedia editor considers with every edit. Is this NPOV? Is this a COI violation? Is this violating the BLP principles? The sort of things that Wikipedia editors care about are so much more detailed and delicate than what the law can handle.

Conversations about content moderation that are happening right now will shape the future of the internet. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights held a session about content moderation and free expression, and the Public Policy team was there to talk about how the right of communities to moderate their own content is absolutely essential to the functioning of Wikimedia projects. We know that government decisions about content moderation have the potential to trample on nuanced community policies that have made Wikimedia projects successful.

We are protecting the work of every Wikimedia editor into the future. We are also trying to make sure that other platforms similar to ours are able to develop and flourish. At the end of the day, if we just protected our projects and got our own exception for everything, that would be a massive loss for the mission and the vision of the Foundation and the movement.

Q: As someone who lives and breathes internet rights policy, what do you think is the biggest threat to the online free knowledge ecosystem in the coming years?

SS: There is this growing idea out there that the internet is a global system by accident, and that bytes crossing a border should be subject to the same types of restrictions and protocols as a person crossing a border. Governments are beginning to create and enforce national internet standards based on their own definitions of decency, or sovereignty. Before, we might have considered a speech-restricted regime as being an isolated case, but this practice is growing.

We are tracking different proposals in different countries that were pretty clearly a reaction to criticisms of the government. If you had no context of political situations in those countries, you could think those bills were perfectly innocent because they use the same language and justifications and mechanisms as bills in places that rank high in protection of free expression. The question is: who is wielding those mechanisms? Wikimedia communities have long prided themselves on the projects having the same content no matter where you are in the world–if you speak Spanish, you’ll get the same Spanish Wikipedia anywhere. This is already a challenge, and this is likely to become a bigger challenge for us in the near future. This is why it is so important for us to continue to be deeply involved in internet policy as it is being shaped globally.

Learn more about the Public Policy’s efforts on their Public Policy Portal.

*This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation