Retention of knowledge on encyclopedias like Wikipedia is a tricky task. It revolves around a set of ideas including systematic bias, and thus becomes a tedious job for passionate contributors who are willing to contribute but do not have enough guidance on “how to navigate this”, perhaps because they are new to this ecosystem. In the previous strategic learnings, DCW researchers shared with the wider community the ideas, and practices relevant to retention of contributors, formation of productive programs, and those related to institutional partnerships, and organizational structuring. DCW’s six monthly research study on finding a strategic trajectory for its development has come to its conclusion but it has not ended in essence. These research scholars would continue guiding people in this ecosystem of knowledge-sharing with the best of their knowledge and skills.

DCW Researcher Namrah Shareef focused on and tried to look for the ways that could be utilized in the process of having the “sum-total of knowledge freely available” because the existence of the ideas like systematic bias appear to be big barriers in this process. She also asserts that the limitations that the notability guidelines on Wikipedia projects put forth are contradictory to the vision statement of imagining a world in which every single person on the planet is given free access to the sum-total of all human knowledge. We need to keep in mind that notability guidelines and similar policies help us filter spam and self-advertisement and what does not belong truly to an encyclopedia. However, Runa Bhattarcharjee, who works with the Wikimedia Foundation, feels that these guidelines are not inclusive of oral history citations. She says that, “these are traditional knowledge systems with their own system of notability and need to find an aligned notability transition point that helps with retention of that knowledge for further reuse in systems like Wikipedia.” Her statement is sensible since, for instance, “YouTube or social media apps are easier to access for many, and they can make these into videos or posts on these platforms as original content, but it needs further connections into say research papers or other reliable publications to be ready for Wikipedia.”

Filtering spam and self-advertisement is a necessary thing, and this makes platforms like Wikipedia more credible and reliable. However, the non-inclusiveness of traditional knowledge systems in them creates difficulty in retaining contributors from areas and regions where mainstream media and so-called reliable sources do not discuss a lot of knowledge, or happen to contain misinformation, or simply do not exist, for instance, in case of some tribal areas where the only reliable source on the tribe’s history is a certain leader or a scholar, who inherited this knowledge from his predecessors, and thus forming a chain or “oral history citations”. This would necessarily be not coming from a verified news organization and could be a self-published YouTube video which does not meet English Wikipedia’s standard of “reliability“. Namrah believes that notability and resource-verifiability guidelines (even if they are consensus-based) hinder a lot of knowledge, and they need to evolve subject to Movement Strategy Recommendation #41: Policies that hinder knowledge equity, because they stop a lot of knowledge from areas where having a verifiable, print or online, or a scholarly resource may not be potentially available. This evolution could likely be a step towards imagining a world where everyone has access to the sum-total of all human knowledge.

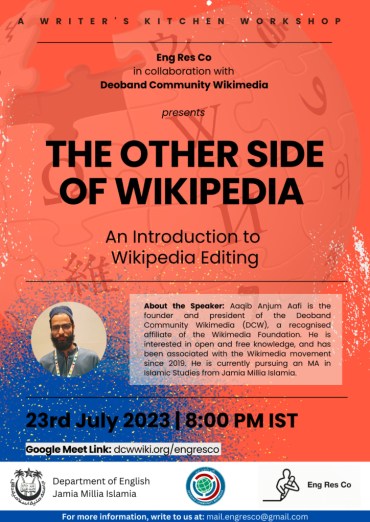

Systematic bias plays a major role in hindering knowledge. Namrah suggests that Wikimedia affiliates and mission-aligned organizations should navigate through every road of this bias, and try to bridge the gap. This could be achieved by knowledgeable people by means of training and awareness initiatives. At the DCW, we are trying to collaborate with some institutions to create this awareness and involve students and scholars into knowledge-sharing processes. On 23 July 2023, we co-organized an e-workshop titled The Other Side of Wikipedia with English Researchers Collective at the Jamia Millia Islamia

The Other Side of Wikipedia aimed to explore the vastness of Wikipedia on the other side – the common side being the reading, and the participants showed an interest in contributing to the sum-total of knowledge. If we do not share what we know, no one else can, since they do not know the truth. It is necessary that we involve more people from our communities and regions and teach them the ifs and buts of the encyclopedia, as a start point.

DCW also co-organized an on-site workshop on Digital Literacy Empowerment in partnership with Bayt al-Hikmah, in Deoband, on 26 July 2023, with an aim to engage the students from there in the world of knowledge-sharing. This process does not only help us represent our legacy at a global level but also increases our skills that we could utilize in our betterment with respect to digital empowerment.

Events like this should be regularly organized and contributors should be valued and engaged in productive programs. On 23 July 2023, the DCW initiated Heritage Lens, a global photographic initiative which aims to document Muslim heritage within Wikimedia projects. This name was ingeniously coined by Munazza Anjum, who leads the Advancement and Communications at the DCW.

DCW believes that “Photography is an important skill, and is as much part of “knowledge” as is any book or a journal. Sometimes it speaks more than what a mere text could do.” Namrah suggests that Wikimedia affiliates should invest in such initiatives but respect the community resources. These resources are to be spend on knowledge, and not on leisure, she asserts.

Needs assessment initiatives help us know and analyze the needs and requirements of communities, people, and areas, where we are supposed to work and carry on our projects. Researcher Amrit Sufi, believes that “Needs assessment is essential since there are diverse forms of knowledge all over the globe, not to mention how knowledge is shared culturally, strategies and sensitivities are needed to preserve and disseminate them. Assessing needs ensures that required resources are made available to interested communities, and also the acknowledgement that singular solutions might not be as effective as the solutions elicited upon in-depth conversations with and observations of stakeholders.” DCW recommends formulating needs assessment initiatives. A good example of this could be WikiFact Checkers, a project that has been initiated from the African part of the world. They put efforts to increase media participation in Wikipedia in order to improve the quality of material and address the content gap and deficiency. They believe that the media belongs in the Wikipedia community.

Systematic bias could be reduced and notability guidelines may evolve but it is difficult to allow each and everything on an encyclopedia like Wikipedia until and unless it meets a certain standard. These standards are justified but at the same time they hinder knowledge. It is a good time to explore alternate approaches to knowledge-sharing, thematic or non-thematic, oral, or text-oriented. This can help us create a world in which we can rightly and truly imagine every other person.

With these recommendations related to knowledge retention, DCW researchers suggest that Wikimedia organizers should not limit themselves to the Wikimedia ecosystem. Knowledge must and should be shared in all possible forms and formats, so that every other human gets equal access to knowledge. This concludes DCW’s strategic trajectory research project, and we are hopeful to make a book out of this anytime soon.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation