In this article the Wikimedia coordinator of the KB, the national library of the Netherlands, explains why he decided to migrate all KB’s Wikimedia-related publications of the last 13 years from SlideShare to Zenodo, while retaining copies of them on Wikimedia Commons.

As the Wikimedia coordinator of the KB, the national library of the Netherlands, sharing knowledge is an integral and important part of my job. Not only live during events, but also for knowledge reference and sustainability purposes after the events have ended.

Wikimedia Commons

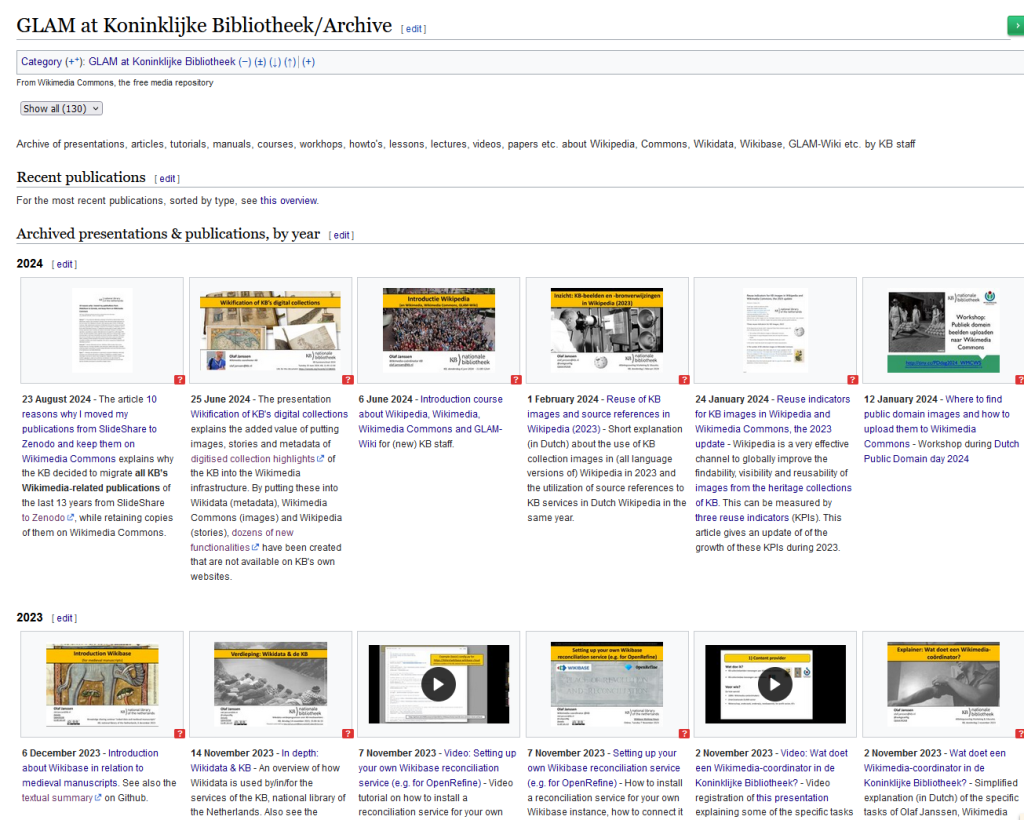

This is why I make all Wikimedia-related presentations, articles, reports, workshop materials, tutorials, videos and other publications available in the Dutch and English bilingual KB Wikimedia presentations & publications archive on Wikimedia Commons. I’ve been doing so for the last 13 years. This ensures all such KB content:

- can be easily found via search engines (Google loves Wiki),

- is available for reuse in the 700+ Wikimedia projects and communities,

- can be reused freely by the entire world because open (Creative Commons) licensing is mandatory,

- can be used as linked open data, independent of language, because multilingual Structured Data has been added to many of these files,

- is stored in a durable way; this year, Wikimedia Commons is celebrating its 20th anniversary and future financing and governance look strong.

SlideShare and new needs

In addition to Wikimedia Commons, I also used to upload my outputs to SlideShare. When I started doing this 14 years ago, my publishing and sharing needs were relatively simple and naive, with visibility and findability being the main purposes. Back then, SlideShare met this need, as it is well-indexed by search engines, has a visual-first user experience, and can be embedded into LinkedIn and Twitter posts.

At that time I had no need for (or awareness of) more advanced functionalities, such as

- Sharing a wider variety of file formats, beyond the typical “presentation oriented” PDF and JPG, such as more “data oriented” formats like JSON, TSV, Markdown, Jupyter notebooks or zipped OpenRefine project files.

- Publishing constituent workshop materials under one unique and persistent identifier – i.e. making all slides, notes, guide for participants, CSV with data, Jupyter notebooks or OpenRefine files used for a typical (data)workshop accessible as a combined package via a single URL.

- Sharing large files, such as video recording of live presentations of 100s of MBs, or entire datasets of hundreds of hi-res images and their descriptive metadata files.

- Adhering to FAIR principles.

- REST APIs to interact with the publications programmatically.

- OAI-PMH connectivity for exchanging publications with other repositories.

Although Wikimedia and/or SlideShare can meet some of these needs, over the years I gradually found out that they were not really potent enough to meet my ever increasing publication needs for my work to be discoverable and reusable by as many people, institutions and machines as possible, now and in the future, in a durable way, with low risk of their URLs becoming 404s or not findable at all.

Furthermore, the KB is a scientific institution and thus part of the international science and research communities. So as an employee of such an institution, I felt a need to also make my publications more strongly integrated into these communities. Both Wikimedia Commons and SlideShare fail to meet this need, neither of them has a strong user base in academic publishing.

Finally, as a European user of SlideShare, without going into all (legal) details, I felt some stress about having my content hosted on servers located in the US and being under that jurisdiction. This stimulated me to look for strictly EU-based hosting alternatives.

New publication strategy, including Zenodo

The new needs and insights I developed over these years slowly but surely urged me to change my approach to storing and sharing my content. As the KB has been a part of the Wikimedia community for many years, an important requirement was to keep all Wikimedia-related KB output available through Wikimedia Commons.

However, for the KB content hosted on SlideShare, I needed to find a better place, closer to home, on EU-based servers, with a service meeting as many of my demands as possible.

After doing some (non-exhaustive) comparison, using the Generalist Repository Comparison Chart among others, I picked Zenodo as the best match for my needs.

In summary, Zenodo is a general-purpose EU-hosted data repository built on open-source software that accepts all forms of research output, including presentations, research papers, data sets, research software, reports, and any other research related digital artefact. For each submission, a persistent digital object identifier (DOI) is minted, which makes the stored items easily citable.

My choice for Zenodo was also influenced by my wish to comply with KB’s earlier choice of Zenodo as its preferred repository; employee-generated publications have been stored in its KB community since 2017.

Gradually I started moving my Wikimedia-related content from SlideShare to Zenodo. Along the way I also improved and harmonized the descriptions and other metadata associated with the files. Of course I made sure to submit all my content to the KB community as well. I completed this task in the summer of 2024, making all these presentations, articles, reports, tutorials, videos and other publications now accessible from Zenodo.

My Top 10 Zenodo features

Let us now look at the ten Zenodo features that are most relevant for meeting my personal needs and wishes, in comparison to SlideShare and Wikimedia Commons. I have no ambition to discuss the complete feature set Zenodo has to offer; if you are interested in that, you can check Zenodo’s detailed public About, Principles, General Policies, Privacy Policy and Infrastructure documents.

The 10 advantages of Zenodo most important to me are :

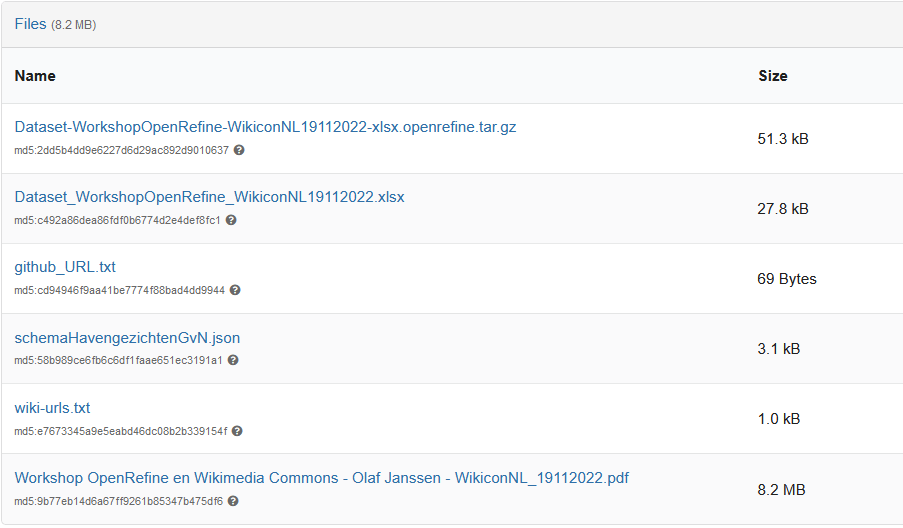

1) Sharing a wide variety of file formats, beyond the typical “presentation-oriented” PDF and JPG, such as more “data-oriented” formats like JSON, TSV, Markdown, Jupyter notebooks, or zipped files. Zenodo is very flexible, as it supports uploading files in any format. Wikimedia Commons has a smaller set of supported formats and SlideShare only allows PowerPoint, PDF and Word files.

Example: The Workshop OpenRefine en Wikimedia Commons (19-11-2022) hosts files in tar.gz, pdf, xlsx, txt and json formats.

2) Publishing constituent workshop materials under one unique and persistent identifier. When running a typical data-oriented workshop, it is very convenient – both for the participants and for post-workshop archiving – to publish all materials (slides, notes, guide for participants, csv with data, Jupyter notebooks, Openrefine project files, etc.) as a combined package in a single location under a single durable URI or DOI. This is a real added value of Zenodo, as both SlideShare and Wikimedia Commons allow only one file per upload.

Example: This OpenRefine Introduction Workshop (2023) packages six files (pdf, xlsx, txt, and md) into a single upload.

3) Sharing large files, with personal use cases including video recording of live presentations of hundreds of MBs, or datasets containing large numbers of hi-res images and their descriptive metadata files (1+ GB). SlideShare has a 300MB limit and Wikimedia Commons allows 100MB by default, or up to 5GB when using chunked uploading. Zenodo has a default 50GB file size limit for each publication, which is more than enough for my needs.

Example: Hosting the 397 MB video Wikidata in de praktijk bij de Koninklijke Bibliotheek, masterclass Wikidata (28-05-2021) is well within Zenodo’s file size limits.

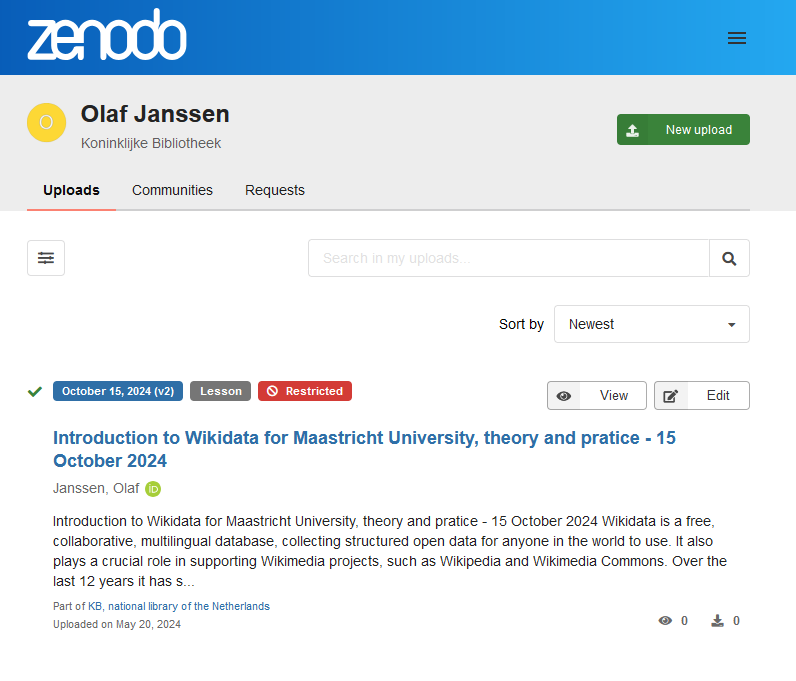

4) Restricting access to files and saving drafts are features in Zenodo that allow editors to work on (drafts of) records in a closed-off environment before releasing them to the public. Wikimedia Commons does not offer this, as every file there is publicly accessible, and under version control right from the start, making it unsuitable for drafting temporary or permanent non-open publications.

Example: I’m currently preparing a Wikidata introduction workshop for Maastricht University and already uploaded some draft materials for this event to Zenodo. When the preparations are finished, I will openly share the files with the participants via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11224632

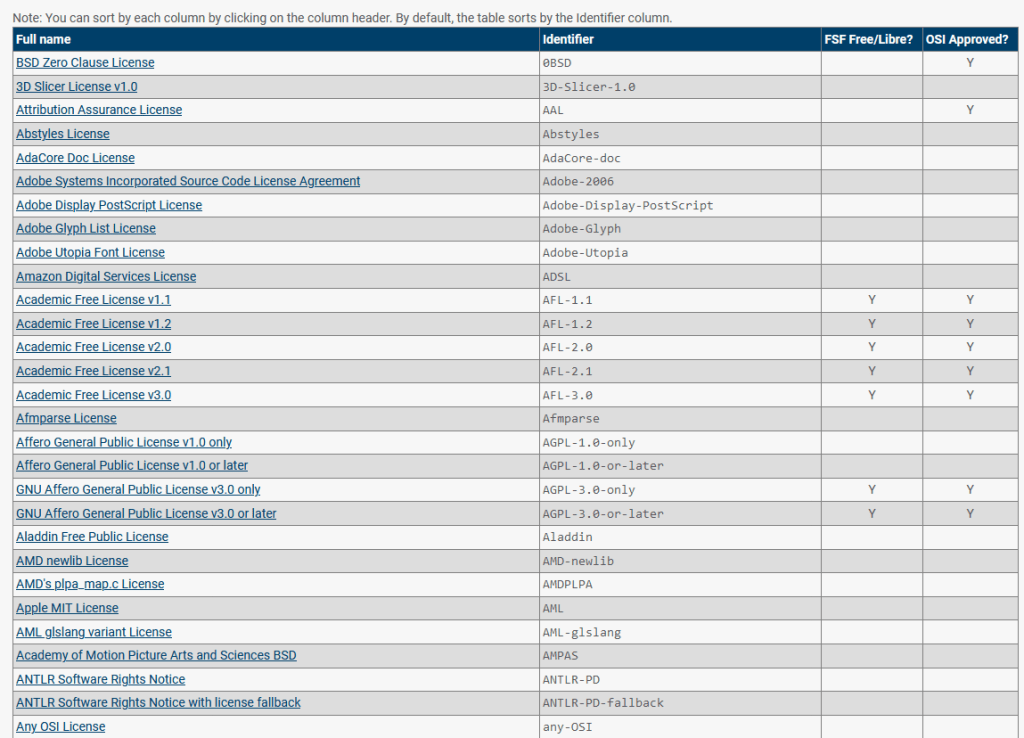

5) Wider licensing options compared to Wikimedia Commons and SlideShare. By default, I publish and share my content under open licenses, either CC-BY, CC-BY-SA or even CC0. This makes my publications suitable for Wikimedia Commons as well as for SlideShare.

However, in some cases, I would like to have a bit more control over derivative or commercial reuses of my works, for which CC-BY-ND and/or CC-BY-NC licensing are appropriate instruments. This makes these kinds of works unsuitable for sharing on Wikimedia Commons, but SlideShare would still be an option, as these more restrictive licenses are allowed there.

Zenodo accommodates all of the above scenarios, as it allows for both very open (CC0) and less open (CC-BY-NC/ND) licenses, as well as over 600 alternative options, both for presentation-oriented and data-oriented publication. So in the vast majority of cases, there is always a suitable license to choose from.

The only exception is the ‘All rights reserved’ case. It is allowed by SlideShare, but not on either open-oriented platform. However, I can use this limitation of Zenodo and Commons as a stimulant to always create publications that are suitable for sharing (be it under a CC-BY-ND/NC clause) and reuse when possible (without the ND clause).

6) Adhering to FAIR principles. Zenodo’s Principles page explains in detail how the repository adheres to the FAIR principles of being Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable.

This makes Zenodo more FAIR-compliant than Wikimedia Commons. Although all uploads get their own unique persistent M-identifiers (so-called Concept URIs, such as https://commons.wikimedia.org/entity/M144836996), these play a less manifest and significant role than their DOI equivalents in Zenodo. Multilingual findability is limited by the English-oriented category names used to group files.

On the positive side, metadata of each upload is indexed and searchable via the Wikimedia Commons search engine immediately after publishing. Additionally, all files and their metadata can be requested for free via a set of REST-APIs without the need for a user account.

However, interoperability is non-ideal as Commons uses metadata standards that are not necessarily compatible with ontologies in the cultural heritage and humanities domains. Also Commons does not offer support for standards like IIIF, although some attempts have been made in the past. All Commons files can be reused because open (Creative Commons) licenses are mandatory.

Finally, thanks to the Structured Data on Commons effort, Wikidata has been integrated into Commons. This means all FAIR strongpoints of Wikidata (“Wikidata fulfills the most complete degree of FAIRness”) are now exposed to Commons as well.

As for SlideShare, it is a purely presentation-oriented and visual-first environment, with no explicit attention to being FAIR. It does for instance not use unique and persistent identifiers for its uploads, nor does it offer rich and explicit metadata for them. Publications are not linked to open, external vocabularies, and you will need to have an account to be able to download content and their (very basic) metadata.

7) Durability for files, governance and funding: Zenodo was launched in May 2013 and is hosted as an embedded service of CERN, which has existed for 70 years and currently has programs defined for the next 20+ years. Files are stored with longevity as a primary focus. Additional checks and balances with respect to the infrastructure, servers, storage, security, governance, financing, and legal status all contribute to future-proofing the repository.

This is at least on par with the sustainability of Wikimedia Commons, which has been in operation for 20 years now. It is part of the Wikimedia Foundation portfolio, and as such, is funded and governed by the overall policies of the Wikimedia movement, with durability, transparency, openness and reliability at its core. Long-term funding of its projects is secured by the Wikimedia Endowment, aiming to support Wikimedia projects in perpetuity.

As for SlideShare, it is operated by Scribd, a U.S.-based privately owned company funded by venture capital. Obviously, this is not an ideal situation to ensure long term accessibility of content hosted on SlideShare. This was another reason to migrate my content from there onto Zenodo.

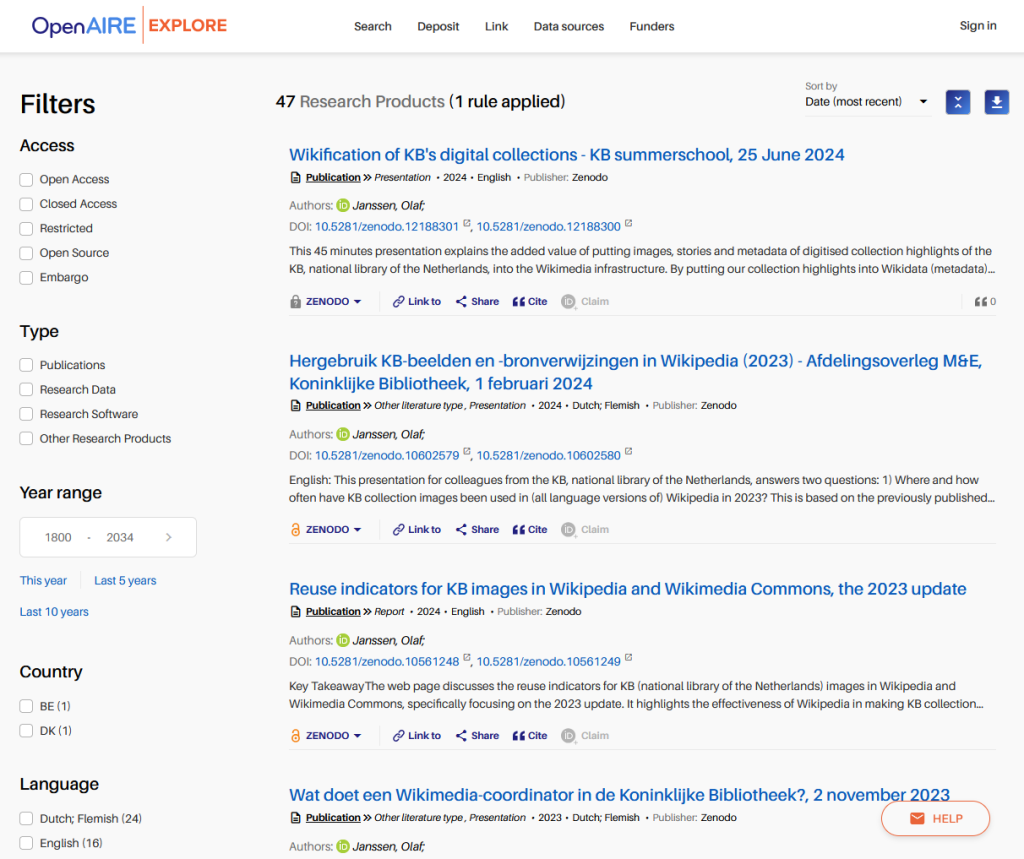

8) Contributing to international research: The KB is a scientific organization and, as such, part of the international science and research communities. As an employee of such an institution, Zenodo allows me to automatically integrate my publications into scholarly aggregators, such as ORCID, DataCite, OpenAIRE, BASE or FID Benelux, making them more visible for study and research purposes, without any extra effort on my part.

Both Wikimedia Commons and SlideShare are not well integrated into academic workflows and don’t have strong user bases in the scholarly community. By exposing my Wikimedia-related publications to this target group, I hope to raise more awareness of the benefits that Wikimedia can bring to their fields of work.

9) Fully hosted on EU-based servers: Zenodo is powered by the CERN Data Centre, physically located in France. This means it is subject to CERN’s legal status as an intergovernmental organization with immunity from the jurisdictions of the nation courts of the EU Member States (source). This effectively safeguards Zenodo from being taken down due to legal procedures initiated by hostile agents.

Although Wikimedia Commons runs in data centers partly located in the EU (Amsterdam and Marseille), the platform legally falls under U.S. jurisdiction, as its operator, the Wikimedia Foundation, is a nonprofit public charity under U.S. law.

10) The REST API and OAI-PMH interface allow for programmatic interactions with my publications. In accordance with the Collections as Data initiative, these APIs allow me to expose my “Publications as Data”, supporting computationally-driven sharing, research and teaching.

Zenodo’s REST API allows publication metadata to be requested directly in JSON format (example) that can be processed further via Python and other languages. For instance, with only a few lines of code, you can request all my publications as an Excel file.

Via Zenodo’s OAI-PMH interface, all publications in the KB community can be requested in various metadata formats, including the library-oriented OAI_DC or MARC21 schemes. This protocol is used by the scholarly aggregators listed in point 8) to ingest KB publications into their repositories.

As for Wikimedia Commons, the MediaWiki software used by this platform offers a set of rich and free REST-APIs allowing for a wide range of machine interactions with my publications. Furthermore, thanks to the Structured Data on Commons effort, all my publications will soon be available as Linked Open Data that can be queried via the Wikimedia Commons SPARQL service. Unfortunately, Commons does not offer an OAI-PMH interface.

SlideShare used to have a REST API, but it seems to have been inactive for several years now.

Downsides of Zenodo

Given all these positive features, you might think there are no downsides to sharing your presentations, articles, tutorials, and other publications via Zenodo. Well, of course there are! Coming from SlideShare and Wikimedia Commons backgrounds, three drawbacks of Zenodo I’ve personally encountered are:

1) Zenodo does not have a vivid community. One of the very uniqe features of Wikimedia Commons is its very vivid community. It means tools, events, meetings, help desk, village pump, discussions, documentation, and all other things Wikimedians have collectively created to make Commons such a valuable a social machine. Zenodo lacks such a group of external contributors advancing and supporting its development.

2) Zenodo is not well known among regular web users, as it is not part of the mainstream internet. Compared to SlideShare, still ranked in the top 600 of most visited websites worldwide, Zenodo is far more long-tail and niche (ranked 55K+). This lowers the chances for my publications to be spontaneously discovered via search engines or social media by general web users.

This disadvantage is however mitigated by my publications also being available on Wikimedia Commons, which has a much better exposure to search engines compared to Zenodo. This makes my presentations findable outside the scientific communication and publication channels.

Furthermore, most of my content is not aimed at the general public, but rather at professional, specialized target groups, including library and digital heritage professionals, data-oriented scholars (digital humanities), and the Wikimedia communities. These types of users will probably be more likely to visit Zenodo (and Wikimedia Commons) than SlideShare when looking for this sort of content.

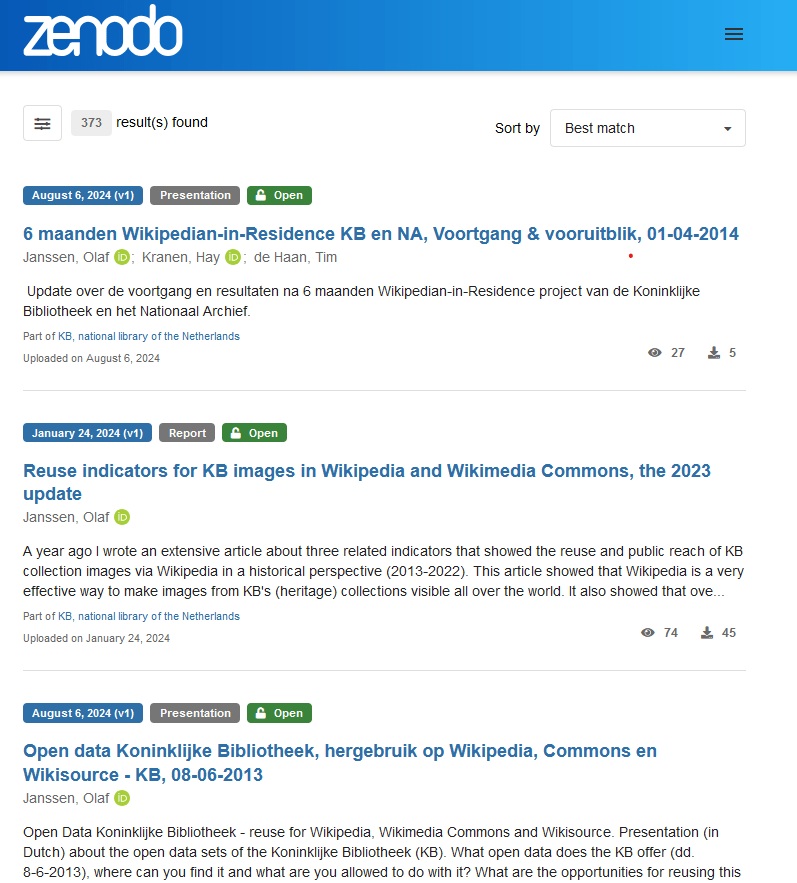

3) Zenodo does not offer a visual-first user experience. This is especially apparent when looking at how search results for the query “koninklijke bibliotheek” are displayed on SlideShare versus Zenodo. The default gallery view used by SlideShare is visually more appealing than the text-oriented display of Zenodo’s results.

For the publications themselves, a typical SlideShare page offers a much stronger visual-first experience than a typical Zenodo record page, which contains much more manifest textual (metadata) elements.

Of course, these differences are hardly surprising because Zenodo was built as a scientific data-focused service, giving metadata the same (or even higher) priority as the object. But for users coming from the visual-first background of SlideShare, where most textual metadata is rather hidden, the differences are striking.

Fortunately, using its REST API and some Python code, it would be very feasible to generate a thumbnail gallery view for all my publications in Zenodo, mimicking the KB Wikimedia presentations & publications archive discussed at the start of this article.

Summary and conclusion

In this article, I describe my journey in transitioning from SlideShare to Zenodo for hosting and sharing my professional Wikimedia-related content, while continuing to maintain KB’s presence on Wikimedia Commons.

As my publishing requirements evolved over time, the need for a more robust, versatile, and research-oriented platform became clear. While SlideShare initially met my basic needs for visibility and discoverability, its limitations—such as a narrow selection of file formats, lack of advanced metadata support, and concerns about long-term accessibility—prompted me to look for a better alternative.

Zenodo emerged as the optimal choice due to its EU-based hosting, support for a wide range of file types, and strong alignment with the FAIR principles of data management. The platform’s ability to mint DOIs, manage large files, and integrate with academic repositories, along with its multi-level sustainability and machine interaction capabilities, significantly enhances the discoverability and reuse of my work within the international research community.

Despite some drawbacks, such as the lack of a vivid community and its less visual-first user experience compared to SlideShare, Zenodo’s strengths in durability, flexibility, and scholarly integration far outweigh these concerns.

In conclusion, Zenodo, in conjunction with Wikimedia Commons, provides a powerful and sustainable solution for managing and disseminating my professional outputs. By utilizing both platforms synergistically, I can ensure that my work remains accessible, reusable, and impactful for a diverse range of audiences, from general web users to specialized academic communities.

About the author

Olaf Janssen is the Wikimedia coordinator of the KB, the national library of the Netherlands. He contributes to Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata as User:OlafJanssen

Reusing this blogpost

This blogpost is based on Olaf’s original article 10 Reasons Why I Moved My Publications from Slideshare to Zenodo, and Keep Them on Wikimedia Commons, which is available on Wikimedia Commons and Zenodo.

That text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution CC-BY 4.0 License.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation