This is the first part in an ongoing series on the function and value of lists in the Wikimedia moment by Alex Stinson.

Successful editathons, campaigns, contests and projects within the Wikimedia movement often start with a list: something to engage, focus and build attention for participants in the activity. Almost every topic area benefits from a list: the Gender Gap (Women in Red or Art and Feminism), other underrepresented knowledge projects (Black Lunch Table or Afrocine), complete sets of knowledge identified by experts (i.e missing butterflies) as well as common topics on Wikimedia projects (like WikiProject Military History’s coverage of destroyers in Majestic Titans).

Except for the most experienced Wikimedians, finding an article to edit — especially in a theme or area that you don’t contribute to often — can be challenging. You both need to learn what is notable for that topic area and learn the research tactics for finding verifiable knowledge in that domain. While learning that knowledge you have to wade through the existing content to identify what has been covered, what hasn’t, and where to start. Lists of missing content are some of the easiest ways for one Wikimedian to help another: they show where the gaps are, build a foundation for working through a backlog of tasks, and can be the foundation of collaboration.

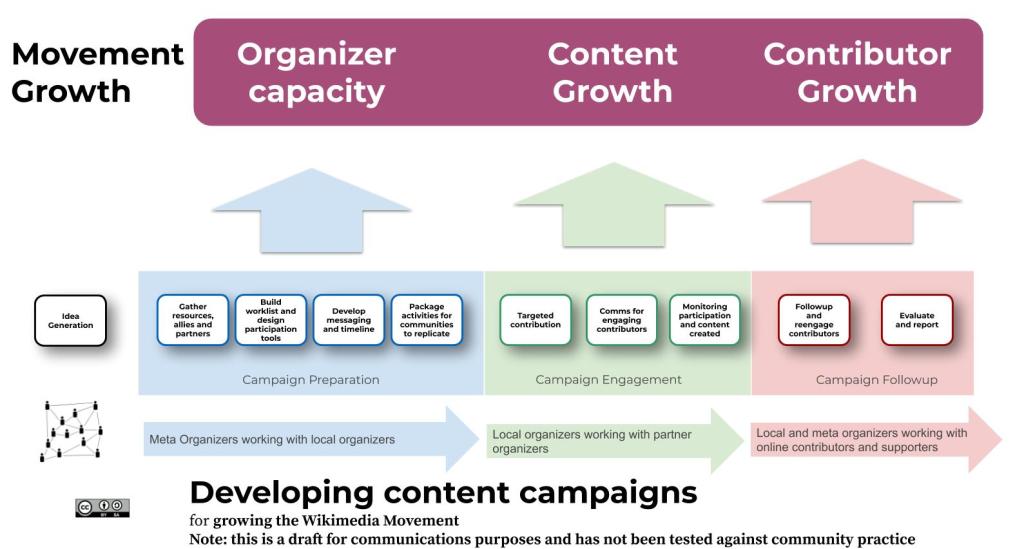

In documenting the practices that volunteers use to run content campaigns and other outreach tactics in the Wikimedia ecosystem I’ve observed that list building is both an art and a science — something that combines intuitive understanding of the Wikimedia knowledge ecosystem, familiarity with external sources of knowledge, and a deep understanding of the tools and practices for sorting through that content. In short, list building feels dependent on either very experienced Wikimedians or an expert or librarian with support from the Wikimedia community. In this four part blog series, I am going to explore the why and how of list building in the movement to make it easier for newer contributors to build effective lists.

Why are lists so important?

When the scope of Wikimedia projects is all human knowledge in all languages — one of the most daunting tasks for many folks is “where do I start?”. Wikimedia communities have tried a number of different tactics for surfacing places to start, such as tagging individual pages with maintenance templates, but one of the most effective tactics for helping both experienced and new editors to participate is creating topically-focused lists. Lists turn a potentially never ending task into something that the community can track progress against, and defines what the “scope of participation” looks like.

In a way, list building is like any other form of idea generation or outlining for knowledge production projects, like writing a book, building a curriculum for a classroom, or designing a museum exhibition. List can help with:

- Developing shared aspiration: First, defining the scope of lists helps define a shared aspiration about what you hope the end-user to see, motivating and energizing participants with the “so what?” of the project. In the case of a museum exhibition: which artists represent the kind of art we value? What kinds of visual storytelling do we want to share with the public?

- Focusing a group: Second, once the list is created and agreed upon by a group of collaborators, it can help keep everyone focused on the task. For example, when I am developing a curriculum with other teachers or instructors, the list both helps us identify the core materials that we need students to read, the different parts that we need to develop together, and helps make sure that we each do our part.

- Inviting less knowledgeable participants: Lastly, lists help make it easier for the less experienced participants to “show up” and choose something to do. For example, when compiling a textbook or White Paper, often graduate students or subject matter experts contribute parts identified in an outline-focused list. In the Wikimedia space, you need different skill sets to build the list and run a project, like an experienced book editor, as opposed to being a contributor.

Additionally in Wikimedia, a lot of contributors are “free agents”: they take a lot of joy in the process and community of creating knowledge on our platforms, and are topic agnostic contributors. If a community, like Black Lunch Table or GLAM experts, propose a list of topics these free agent editors can contribute against the suggested list. Most on-wiki writing contests appeal to these experienced Wikimedians with similar tactics.

When do you see lists?

List building can be both a collective or individual activity — and we see both quite often in the Wikimedia ecosystem.

On the individual front: experienced Wikimedians frequently collect pages in their user space that describe things that they want to work on. These private to-do lists help make it easier to come back in the spare bits of time that they have for volunteering. For example, most folks that I know working on the #100WikiDays challenge keep a list of topics they discover while browsing Wikipedia or during events to come back to when they are spending the 20-30 minutes a day it takes to create a stub article.

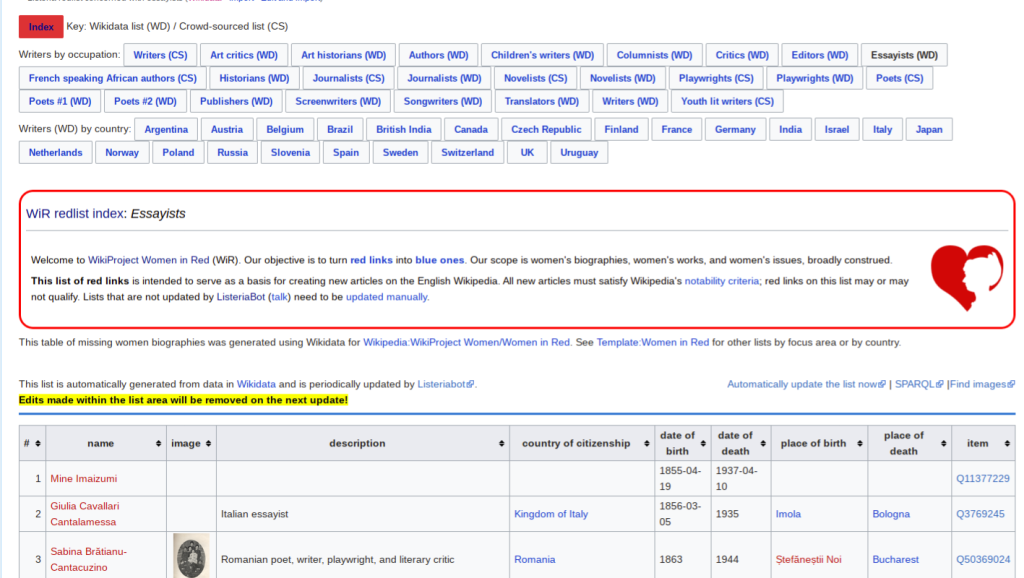

List building has added layers of complexity when groups begin to generate lists. Almost every healthy WikiProject on English Wikipedia starts with list building: Women in Red, WikiProject Medicine, Women Scientists, and WikiProject Military History thrive on knowing what is “in scope” and where potential missing topics exist. The arrival of more complex tools like Wikidata allows for these “potentially in scope” lists to be generated on the fly based on data collected by others. These lists drive everything from quality improvement drives of Medical content for translation into key local languages, to writing new content to fill the gender gap.

Building gap lists is also a really compelling way to engage librarians and content experts without asking them to learn the ins and outs of Wikimedia contribution. Almost every editathon I support includes a librarian or local content expert identifying topics relevant to their expertise and collections, making them better sponsors of the event.

For GLAM institutions and scholars, a Wikimedia list may be one of the first times they have assessed their knowledge and expertise in light of Wikipedia’s broad public audience (“what is a general knowledge encyclopedic topic?”, “how do I identify gaps in Wikipedia related to my expertise?”, etc). The continually growing list maintained by the Pritzker Military Museum and Library in Chicago has become an over half decade exercise in identifying the most publically relevant topics and materials in their collection and surfacing them for a public audience.

For education assignments, where students write Wikipedia content, picking a list of topics has been one of the things we recommend to almost all educators from as early as 2010: because students are both learning Wikipedia and the field they are researching for assignments, faculty and Wikipedians delivering a list of “good topics” gets them started on the best research in quick targeted ways. More recently, lists have been really important for large-scale collaboration in Education: in Armenia, the community is digitizing books for WikiSource based on a list of works in the curriculum, and the Basque community is supporting college students in writing content that is core to the national curriculum.

Let’s learn how!

I think our community leverages the function of list building in the Wikimedia ecosystem intuitively, but I have yet to find a good “manual” for understanding what the options are and picking a tactic. I am going to use the next three blog posts to highlight those functions, from the manual list, to leveraging content on the platforms to create lists, to using semi-automated tools based on Wikidata and the other data on Wikimedia projects.

Lists in the Wikimedia movement Part 2: Building manual lists using the editorial practices of the Community

Like this blog series on lists? We need your help documenting list building practices and imagining new and more powerful ways to leverage the list building practices we have so far in the community: how would you make the lists more portable? What kinds of lists or data would you like to collect? If you do something I haven’t covered yet, let me know by reaching out directly via astinson@wikimedia.org, leaving a comment on this post, or sharing the examples on the talk page of the Organizer Framework for Running Campaigns.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation