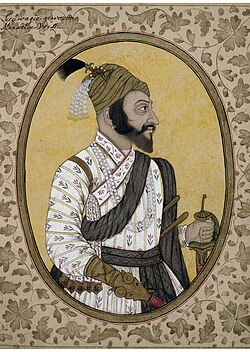

Shaniwarwada palace fort in Pune, it was the seat of the Peshwa rulers of the Maratha Empire till 1818. Image by Ashok Bagade, freely licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

As the Maharashtra Granthottejak Sanstha (MGS) celebrated its 121st anniversary recently, the organization re-licensed 1000 books under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license so that the books could be digitized and be made available on the Marathi Wikisource for millions of Marathi readers.[1]

MGS is a non-profit organization working for the preservation of Maharashtra’s linguistic and cultural heritage. It was founded in Pune, India in 1894. Being an important archive for the preservation of many hundreds of years old manuscripts and historical artifacts from the Peshwa era, the institution is open to public for study and research.

During the four-day anniversary celebration, the Centre for Internet Society’s Access to Knowledge program (CIS-A2K)—an organization that supports the Wikimedia movement in India—opened a Wikipedia stall there where Marathi Wikimedians were present. Around 600 people visited the stall and learned about the news of MGS’s book donation.

Many active and new Marathi Wikimedians were present at the exhibition stall along with Abhinav Garule from the CIS-A2K program to share the incredible work Marathi Wikipedia and Wikimedia community at large are doing. Autographs of eighteen notable writers who received awards from Sanstha for different genres of writings were collected for uploading to the Wikipedia pages about them. While meeting the authors, Wikimedians also approached them to relicense some of their works under Creative Commons licenses so that they could be digitized on Wikisource and/or enrich Wikipedia—and some of the authors expressed a good deal of interest in opening up their books for Wikisource.

Some of the major books donated are Peshwa Rojnishi (diary of Peshwa), Benjamin Franklin Charitra (The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin), Kekavali, S M Paranjape Charitra (autobiography), Letters Exchanged between the Sanstha and the British Government, Shinde Gharanyacha Padmamay Itihas (manuscript), and Marathwadyatil Arvachin Marathi Vangmay (modern Marathi literature from Marathwada, a region in Maharashtra) are some of the popular books read by Marathi speakers that are going to be part of the books donated by the organization.

We reached out to Avinash Chaphekar, the joint secretary of the organization, to know more about the state of book publication and readership.

Subhashish Panigrahi (SP): Could you share your ideas of opening these invaluable books for Wikisource? How they are going to be useful for the online readers to learn about the Peshwas?

Avinash Chaphekar (AC): These books are of historical importance and contain information that needs to reach more people; they cover topics that are rarely covered well anywhere else. Right after India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi recommended the autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, as it contains a lot of messages for a common person, a lady walked up to and asked if she could read it in Marathi. Be it such autobiographies or a poetry book like “Kekavali”, such books that were published by the MGS should not be kept closed—many readers are searching for them. We donated 800 of these old books to the Marathi Wikisource because we don’t have large presence in the media or the Internet, so how would any reader who does not know us buy a book? If these books are available online, they can at least find and read them.

SP: Where do you think there is gap between publishers and readers today? Many Marathi books get published every year and if you search on the Internet, which many people today do, you would hardly find much.

AC: Online readership is increasing every day, but when you look at Marathi readers, the majority of them are still buying books. During the exhibitions here (even this year!), there is always quite a rush to buy books. Only the youth and tech-savvy people read online. But most people we meet say that they feel more comfortable holding and reading physical books. Moreover, there is no concrete research validating that most of the youngsters here are accessing information only online. I still feel reading books in a conventional way by holding books in your hands will continue to exist as there is some kind of satisfaction that lies in it.

SP: Did you know that we are going to get these books retyped, meaning that readers will not just be able to read them in their smartphones or computers but they could use the text for republishing the same books in the future? How do you think such a model will be useful for publishers?

AC: At the MGS, we don’t have funds to republish these books, and publishers are not ready to do it no matter how historically valuable the books are—even an incredibly valuable reference book called Marathi Grantha Nirmiti Watchal (the history of creation of Marathi books in Marathi), authored by SG Tulpule and published by us in 1973. This book has detailed information about Marathi publications, even those that existed before printing technology existed. As many such books are not being reprinted, we cannot leave the remaining few copies to perish. Let them go online and reach millions of people.

Subhashish Panigrahi, Wikimedian and Programme Associate, Access To Knowledge, Centre for Internet and Society (CIS-A2K)

Abhinav Garule, Wikimedian and Programme Associate, Access To Knowledge, Centre for Internet and Society

This post is part of the WikipediansSpeak series. You can find more of these posts on the Wikimedia Commons.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation