The Community Wishlist Survey 2022 is over! We would like to thank everyone who participated in this year’s edition and express our special gratitude to those who made outstanding contributions to the survey below the results. We could not have done it without all of you!

Curious about what happens next? Learn about our prioritization process and check out the ranking of prioritized proposals for this year.

The results

Between 28 January and 11 February, contributors with a registered account could vote for the proposals submitted earlier in January. Almost 1600 users participated in the Survey. 467 proposals were submitted, including 142 archived ones, 55 larger suggestions and 270 which competed for the participants’ votes. There were 9554 support votes, including 8387 votes for the competing proposals. Congratulations to everyone involved! The results of the voting are available on Community Wishlist Survey 2022/Results.

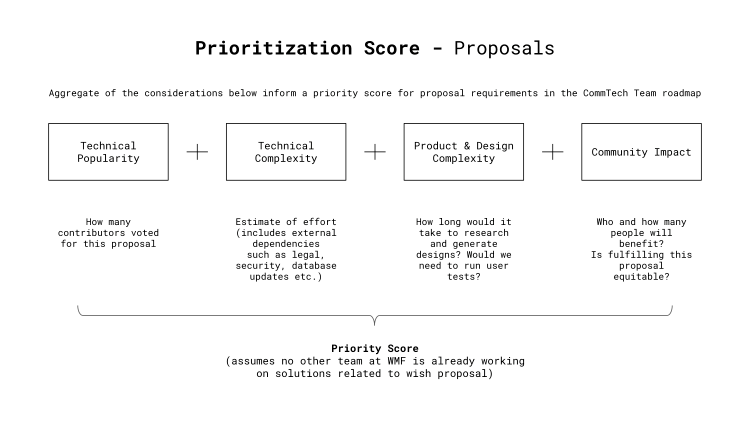

As we wrote on the FAQ page, technical popularity (so the number of votes) is the main factor in the decision which proposals we will be working on. It is an important factor, but not the only one, though. We assessed the top 30 proposals from three perspectives: technical complexity, product and design complexity, and community impact.

This is how we came to the final sequence of projects for 2022!

Learn more about the prioritization

Technical complexity

Our engineers estimate how much effort they would need to put into granting a wish. They prioritize less complex (more workable) projects. Whenever something is not clear, they try to overestimate rather than underestimate.

- Technical dependency – we check if the work requires interactions with other Wikimedia Foundation teams. It could be that part of the work needs to be on other teams’ roadmap or that we need other teams’ input or feedback before we can complete the wish. Examples of these are schema changes, security reviews, adding a new extension, and upgrading third-party libraries.

- Technical research – we ask ourselves if we know how to approach a particular problem. Sometimes we need to evaluate and consider our options before we can start thinking about a solution. Sometimes we need to confirm that what needs to be done can be done or is within what the platform we are working on can handle.

- Technical effort – we ask ourselves how familiar we are with the underlying code and how big or complex the task can be. A high-effort score could also mean that the code we’ll be working with is old, brittle, or has some degree of technical debt that will have to be dealt with before we can start working on our actual task.

Product and design

Similarly to the assessments above, our designer estimates what effort should be made to complete a project. He prioritizes less complex (more workable) projects. Whenever something is not clear, he tries to overestimate rather than underestimate.

- Design research effort – we seek to understand the level of research needed for each proposal. In this case, the research involves understanding the problem, either at the very beginning through initial discovery work (the scope and details of the project, surveys or interviews with community members), or later in the process through community discussions and usability testing (e.g. how do users contribute with and without this new feature).

- Design research effort – we seek to understand the level of research needed for each proposal. In this case, the research involves understanding the problem, either at the very beginning through initial discovery work (the scope and details of the project, surveys or interviews with community members), or later in the process through community discussions and usability testing (e.g. how do users contribute with and without this new feature).

- Visual design effort – a significant number of proposals require changes in the user interface of Wikimedia projects. Therefore, we check to estimate the change of the user interface, how many elements need to be designed and their complexity. For instance, using existing components from our design system or creating new ones, keeping in mind how many states or warnings need to be conceived to help guide users, including newcomers.

- Workflow complexity – we ask ourselves how does this particular problem interfere with the current workflows or steps in the user experience of editors. For example, a high score here would mean that there are a lot of different scenarios or places in the user interface where contributors might interact with a new feature. It can also mean that we might have to design for different user groups, advanced and newcomers alike.

Community impact

In contrast to the two perspectives described above, this part is about equity. Practically, it’s about mitigating the majorities from being the only ones whose needs we work on.

Depending on this score, proposals with similar numbers of votes and similar degrees of complexity are more or less likely to be prioritized. If a given criterion is met, the proposal gets +1. The more intersections, the higher the score. This assessment was added by our Community Relations Specialist.

- Not only for Wikipedia – proposals related to various projects and project-neutral proposals, are ranked higher than projects dedicated only to Wikipedia. Autosave edited or new unpublished article is an example of a prioritized proposal.

- Sister projects and smaller wikis – we additionally prioritize proposals about the undersupported projects (like Wikisource or Wiktionary). We counted Wikimedia Commons as one of these. Tool that reviews new uploads for potential copyright violations is an example of a prioritized proposal.

- Critical supporting groups – we prioritize proposals dedicated to stewards, CheckUsers, admins, and similar groups serving and technically supporting the broader community. Show recent block history for IPs and ranges is an example of a prioritized proposal.

- Reading experience – we prioritize proposals improving the experience of the largest group of users – the readers. Select preview image is an example of a prioritized proposal.

- Non-textual content and structured data – we prioritize proposals related to multimedia, graphs, etc. Mass uploader is an example of a prioritized proposal.

- Urgency – we prioritize perennial bugs, recurring proposals, and changes which would make contributing significantly smoother. Fix search and replace in the Page namespace editor is an example of a prioritized proposal.

- Barrier for entry – we prioritize proposals about communication and those which would help to make the first contributions. Show editnotices on mobile is an example of a prioritized proposal.

Larger suggestions

Thank you for 55 Larger suggestions, nearly 1200 votes you cast for them, and all the comments you added! You dedicated a lot of time, and this is a huge amount of important knowledge for us.

Why did we create this category and what will we do next?

From the beginning in 2015, we have been explaining that the Community Wishlist Survey has a specific scope. Not every good proposal submitted in the first phase can become our project. We avoid committing to something we cannot do.

At the same time, it is impossible (and not fair!) to expect that submitted proposals that were great ideas but out of our scope should end up in the Archive. In past editions, we archived proposals not meeting the criteria before voting. This time, we decided to create the “Larger suggestions” category and put it next to the regular categories. We wanted to respect the effort put into submitting them, and allow you to express your interest in these projects even if we won’t be able to work on them. To avoid misconceptions, we didn’t put the larger suggestions onto the Results page.

Now, having these suggestions and votes, we will be able to understand your needs better. We will share the results with our leaders and colleagues at the Product department of the Wikimedia Foundation. We can’t promise they will work on these projects soon. They will be informed, though, and perhaps will be inspired when making their plans.

Gratitude

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to all participants. The Community Wishlist Survey is your success as well.

Some of you helped us to improve the Survey before it began. Some spent an outstanding number of hours during the Survey. They were translating the documentation and the proposals, discussing the proposals, and encouraging others to take part. Some decided to take part for the first time, and among them, there were some who affected the final results in a way no one could have expected.

We are not able to make a full list of everyone who deserves to be mentioned here. Heartfelt appreciation to everyone who helped us on social media, within their own communities, and was less likely to be noticed by us.

If you have proposals for the next Survey…

…and don’t want to forget them, add them to the sandbox. Proposals saved there do not count as submitted, but they will be in other people’s minds and will be less likely to be abandoned.

Follow us

- You can watch the page with updates about our recent work.

- You can also watch the main Community Wishlist Survey talk page and talk pages of individual projects.

- Current status of individual wishes is available in form of a table on the main Community Wishlist Survey page.

- Once a month, we hold online meetings called Talk to Us. These meetings are open to anyone.

Thank you!

Natalia, Karolin, Dayllan, MusikAnimal, Sam, Harumi, Szymon, Nicolas, Dom, Ima, and James – Community Tech

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation