Sometimes it can feel as if the world is changing more quickly than ever, and it’s easy to forget that we’re living at the very forefront of a historic timeline of knowledge creation that has evolved through centuries and across cultures, languages, and technologies.

The Wikimedia Foundation recently hosted three “brown bag” discussions with experts on the evolving history of knowledge sharing, providing valuable context for understanding the modern challenges of today and the opportunities to sustain and build the global Wikipedia community of tomorrow. Each of our invited experts (Panthea Lee, Adam Hochschild, and Uzo Iweala) echoed key aspects of other projects which the Foundation has organized as part of its broader effort to understand the future of Wikimedia.

Below is a summary of the two major themes which came out of the discussions, each of which has been posted with the full videos and transcripts.

Our trust in both the sources and methods of distribution of information continues to evolve. People have shifting attitudes toward the trustability of traditional knowledge institutions and more often prefer to use personally-tailored channels to discover and share information with people we trust. This is especially true of younger readers, a focus of our discussion with Panthea Lee, lead designer at Reboot, a research design firm that helped launch the New Readers project in Nigeria and India.

“We see a lot of young people following vloggers and bloggers … that have built up trust in certain ways that may not see Wikipedia content as credible or easy to use,” Lee mentioned, noting that a possible future aspect to the Foundation’s work might build ways to incorporate modular Wikipedia resources and tools into channel-based communities where younger readers discover, create, and share information they trust with people who they trust more than traditional publishers.

Weakened trust in traditional education institutions may be accelerating an interest in personal knowledge creation and sharing, as well. “People are hungry for alternative sources of knowledge,” said Uzo Iweala, a physician, author, Foundation advisor, and CEO and editor-in-chief of Ventures Africa.

Expanding to new readers can also carry a challenge of verification. Sources of knowledge that may be considered of lower value in certain communities, like oral storytelling, are trusted, primary sources in others. Iweala shared a personal example: “We can trace back [my own lineage] to maybe the 1400s, but no one would believe because the start of that is in the 1800s, when the British came in and started keeping paper records. But the stories go back way, way further.”

Creativity in the face of obstacles can inspire brilliant new methods of knowledge sharing. Adam Hochschild, co-founder of Mother Jones, reviewed the history of knowledge sharing, providing a few powerful examples of how people have created solutions to information-sharing barriers.

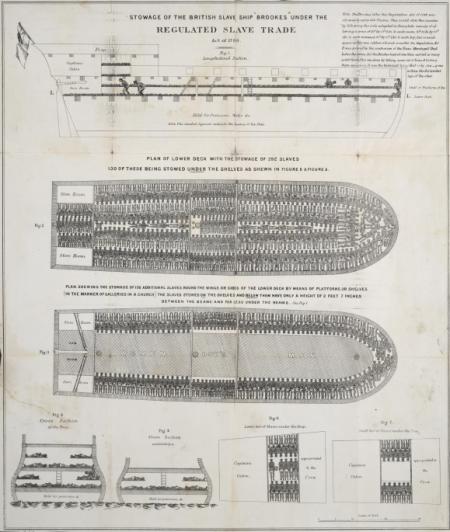

Hochschild pointed to his study of London in the month of February 1788, where “half the debates on record are about slavery or the slave trade.” Adam wanted to know what caused the dramatic spike in the recorded discussion of slavery. His search led him to discover a remarkably brilliant use case in format-based activism.

“A very well organized small group of ardent abolitionists began experimenting” with use of pamphlets and inspired the creation of a famous poster (below), he told us, depicting the stowage of the British slave ship Brookes under the regulated slave trade act of 1788.

Hochschild said that the poster helped strengthen the public support to end slavery:

| “ | The printing of black and white graphics had been around, you know, for a century. But they began using this for their purposes, and one result of all that you’ve seen as a famous poster of a slave ship … You read memoirs from this period and you find many people writing about the impact it had on them when they first saw the slave ship poster. | ” |

In a more modern example of innovation in storytelling-based solutions to recording and sharing knowledge, Hochschild pointed to The People’s Archive of India, which documents exactly the kind of information that local news organizations have avoided historically, such as traditional songs which scholars can now use for research.

It’s a bit overwhelming to think about all the stories which have never been shared only because there isn’t a way to do so yet. The good news is that history, and the work of communities around the world today, show that it’s possible to build a future for knowledge sharing across new generations and cultures. All we need is creativity, dedication, trust, and an acknowledgement that things will change again.

Have you changed the way you discover and share information you trust? We invite you to learn how to join us in the discussion about the ways we participate in knowledge sharing, and tell us about the challenges you face (and your favorite creative solutions).

Margarita Noriega, Strategy Consultant, Communications

Wikimedia Foundation

Videos and transcripts from each brown bag are available on Commons.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation