Languages and multilinguality have always been an important part of the Wikimedia projects. After all, Wikimedia projects are available in over 300 languages. But most of these languages are accessible as a form of knowledge of their own only in their written form. Lingua Libre aims to change that by making the sound of a language and its pronunciation freely available in the form of structured data. Jens Ohlig interviewed Antoine Lamielle, main developer of Lingua Libre, about his project and how it uses Wikibase.

———

Jens: Could you introduce yourself? What brought you to the Wikimedia project?

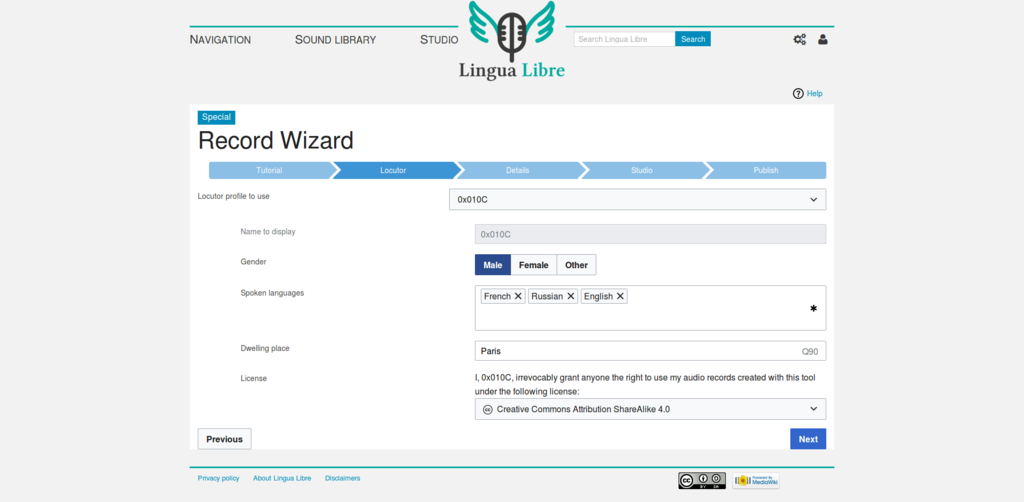

Antoine: I’m User:0x010C, aka Antoine Lamielle, a Wikimedia volunteer since 2014.

I started editing a bit by accident, convinced by the philosophy of global free knowledge sharing. Over time, I’ve become a sysop and checkuser on the French Wikipedia, regular Commonist, working on a lot of on-wiki technical stuff (maintaining and developing bots, gadgets, templates, modules). Now, I’m also the architect and main developer of Lingua Libre since mid-2017.

Off wiki, I’m a French software engineer, fond of kayaking, photography and linguistics.

———

Jens: Tell us more about Lingua Libre! What is it? What’s its history? What is its status at the moment?

Antoine: Lingua Libre is a library of free audio pronunciation recordings that everyone can complete by giving a few words, some proverbs, a few sentences, and so on. These sounds will mainly enrich Wikimedia projects like Wikipedia or Wiktionary, but also help specialists in language studies in their research.

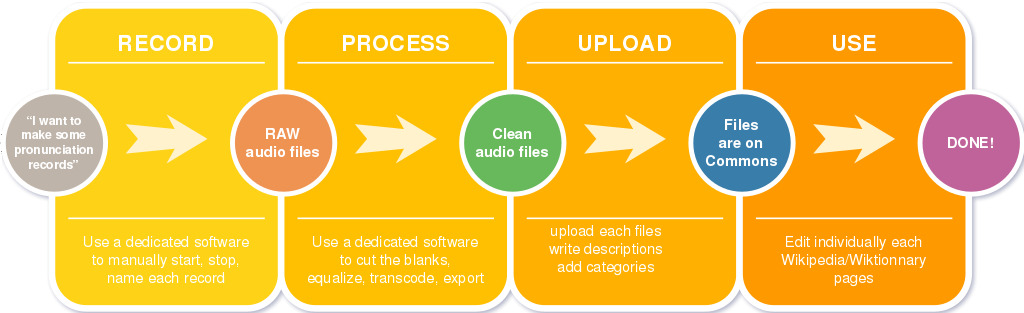

It is a pretty new project, taking its roots in the French wikiproject “Languages of France“, whose goal is to promote and preserve endangered regional languages on the Wikimedia sites. We found at that time that only 3% of all Wiktionary entries had an audio recording. That’s really bad given that it’s a very important element! It allows anyone who does not understand the IPA notation—a large part of the world population—to know how to pronounce a word. From there, the first version of Lingua Libre was born, an online tool to record word lists.

Nowadays, it has become a fully automated process that helps you record and upload pronunciations on Commons and reuse them on Wikidata and Wiktionary. We can do up to 1,200 word pronunciations per hour—this used to be more like 80 per hour with the manual process!

———

Jens: What brought you to Wikibase? Why is it a good fit for Lingua Libre?

Antoine: The first version of Lingua Libre collected metadata for each audio record, but it was stored in a traditional relational database, with no way to re-use it. We wanted to enhance that sleeping metadata by allowing anyone to explore it freely. But we also wished to gain flexibility in easily adding new metadata. Wikibase, equipped with a SPARQL endpoint, offered us all these possibilities, and all that in a well-known environment for Wikimedians! Paired with other benefits of MediaWiki—version history to name only one—the choice was clear.

In our Wikibase instance we store three different types of items: languages (including dialects) imported directly from Wikidata; speakers, containing linguistic information on each person performing a recording (what level he/she has in the languages he/she speaks, and where they learned them, accent etc.); and recordings. These are created transparently by the Lingua Libre recorder for each recording made, linking the file on Wikimedia Commons to metadata (language, transcription, date of the recording, to which Wikipedia article / entry of Wiktionary / Wikidata item it corresponds etc), but also to the item of its author.

———

Jens: Anything positive you realized about Wikibase as a software? Were there any hurdles you had to overcome? Is there anything that can be improved?

Antoine: Using the same software as Wikidata has made it easy for us to build bridges with this project, and take advantage of this incredible wealth of structured data. For example, to allow our speakers to describe where they learned a language, we use Wikidata IDs directly. This has many advantages in our use; so when we ask a new user where they have learned a language, they have total freedom on the level of precision they want to indicate (country, region, city, even neighborhood or school if they wish to), most often with labels translated into their own language.

Backstage we can thus mix and re-use the data of Wikidata and Lingua Libre via federated SPARQL queries (for example to search all the records made in a country, or to be able to listen to variations of pronunciation of the same word in several different regions) and all that without having to manage the cost, the limitations and the heavy maintenance of a geo name database!

However, this is currently more of a set of hacks than a perfect solution. Wikidata items are currently stored as external identifiers in our Wikibase instance, and the entire UI / UX depends on client-side AJAX calls to the Wikidata API. The ideal would be to be able to federate several Wikibases, allowing them to share items natively between them.

———

Jens: Is there something else you’d like to add?

Antoine: Thanks for the amazing job you’ve done so far on Wikibase, hoping it will continue so for a long time!

———

Interview by Jens Ohlig, Software Communications Strategist, Software Development

Wikimedia Germany (Deutschland)

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation