“I used to love that we would shoot for the stars; now I love that I believe we can make it.”

Wikipedia is an indispensable part of the internet — no matter if you’re searching for a fact to win a round of trivia or doing a deep dive on what’s happening in the world around you. And today, the nonprofit organization that supports Wikipedia turns 20 years old.

We are the Wikimedia Foundation. In our work, we support not only Wikipedia but a dozen sister projects and the hundreds of thousands of volunteer editors who edit, expand, and curate them. Together with a number of affiliate organizations, we form the Wikimedia movement, unified by a single mission: a world in which every single person on this planet can access, participate, and share in the sum of all knowledge.

On our 20th birthday, we’re taking stock of where the Wikimedia Foundation is today, looking back at highlights from the last twenty years, and gazing forward to our future.

Who we are today

Jimmy Wales created the Wikimedia Foundation in 2003, two years after he founded Wikipedia.

Since then, we have carried forward the same principles of collaboration and community that have made the online encyclopedia so successful. For example, when we propose making fundamental changes such as creating a sound logo, updating the look of Wikipedia, or implementing a Universal Code of Conduct, we work alongside Wikimedia volunteers to implement them. In fact, our 2011 terms of use update featured a discussion that was longer than the novel Grapes of Wrath.

Our work is not always easy, and sometimes there are disagreements, but our aim is to continue to grow as partners within the Wikimedia movement, seeking feedback and improving on how we can work together on our shared mission. Our commitment to transparency and collaboration means that the end result is often stronger than we could attain alone.

“We work alongside communities of volunteers around the world to enable the creation and sharing of free knowledge,” said Maryana Iskander, CEO of the Wikimedia Foundation. “This global movement continues to keep reliable information available online at a time when it is critically needed more than ever.”

Today, the Wikimedia Foundation supports and celebrates open knowledge, and the volunteers who make it possible, in a variety of ways.

- We ensure that Wikimedia sites stay online and accessible even through the highest of traffic spikes.

- We continually improve the Wikimedia sites so that they are easier to read, more accessible, and inviting for anyone to edit on a variety of devices.

- We fight against censorship and advocate for government policies that ensure sites like Wikipedia can continue providing freely available, crowd-sourced information to people across the world.

- We build awareness and celebrate the work of global volunteer communities.

- We connect with other global institutions, like museums and libraries, and encourage them to share their knowledge on Wikimedia projects through various partnerships and initiatives.

- We provide grants, funding, and other support to people and organizations advancing knowledge equity by closing knowledge gaps on Wikimedia sites.

None of this would be possible without the support of thousands of donors who ensure this work continues.

The early years

When Jimmy Wales announced that he had formed a new nonprofit named the “Wikimedia Foundation” in 2003, his goal was to create a long-term, sustainable future for Wikipedia and other free knowledge projects so people could benefit from these living resources for years to come.

At the time, Wikipedia was run on just two servers. “I think back to the days when I would order a new set of servers and they would get delivered to my house,” Wales said. “I would put them in the back of my little Hyundai, drive down to the data center, get my screwdriver, and put them in the racks.”

Often Wales would then text Brion Vibber, who would become the Foundation’s first full-time employee and is today our Staff Software Architect, to let him know that the new servers were live. Vibber and Tim Starling, our Principal Software Architect, were two of the early developers who contributed to Wikipedia’s growth before the Wikimedia Foundation existed. Both were students who volunteered an extraordinary amount of time towards maintaining the sites when there were no paid staff.

Technical problems began to surface as Wikipedia became one of the most-popular websites in the world. “Wikipedia’s technical infrastructure was in a really dire state. Every day, the number of visitors would climb and things would start to break”, Starling said. To prevent the site from going down, developers would often respond by switching it into read-only mode or disabling key features. Vibber said that the work he did during this time “was absolutely the equivalent of a degree in computer engineering. We hit every problem in the book on the way”.

Wikipedia’s site reliability issues were eventually mitigated through the work of Starling, Vibber, and other volunteer developers.However, as time went on, it became increasingly unsustainable for them to shoulder the load of keeping the website online.

These dynamics drove the early but slow growth of the Wikimedia Foundation, which eventually employed people like Starling and Vibber. In thanks for their significant contributions during those early days, both of these engineers have days “named” after them by Jimmy Wales (see Brion Vibber Day, Tim Starling Day).

Today, the Foundation employs over 300 product and technology staff to address new needs, such as managing 18 billion monthly visits to Wikipedia, maintaining security, and adding new features that make our projects more accessible and safe. And we still welcome all who want to contribute to our open-source codebase.

Upgrading Wikimedia’s usability

Wikipedia and the other Wikimedia projects have been run by communities of volunteer editors since the day they were created. These individuals do the work of expanding, curating, and maintaining millions of articles and other content pages.

As time progressed, we grew to the point where we could take on complex technical work to improve the experience for Wikipedia editors and readers alike. One of those projects started in 2010 with VisualEditor, a way of editing Wikipedia without using blocks of code. In VisualEditor, what you see when you edit is closer to what you get after saving the page.

“Fundamentally, the idea of the visual editor was that there would be a softer, gentler, and more welcoming on-ramp” for new Wikipedia volunteers, said James Forrester, a long-time Wikipedia volunteer who joined the Foundation in 2012 to be VisualEditor’s product manager.

However, building VisualEditor was “perhaps the most challenging technical project ever undertaken in the history of MediaWiki development,” Senior Product Manager Howie Fung said in 2011 (referring to the software that powers Wikipedia). In part, the complexity was because we committed to making it compatible with the existing wikitext editor that had been used since Wikipedia’s inception, and is still used today.

VisualEditor’s beta phase was challenging and filled with bug fixing. In the years since its launch, we continued developing and improving it so that today, it is often one of the first ways in which new editors engage with Wikimedia projects. It formed the foundation upon which we have built a suite of other features aimed at new editors.

Better onboarding for new Wikimedia volunteer contributors

Several of those features have been built by the Wikimedia Foundation’s Growth team, formed in 2018 to create and improve tools for new volunteer contributors. The work of that team has been tremendously impactful in welcoming and retaining new contributors to the Wikimedia projects. For example, in late April 2023 new editors made their one millionth change through the suggested edits feature. Our research shows that this particular feature increases the chances of a new Wikimedia user sticking around by about 12%.

Rita Ho, the team’s Principal User Experience Designer, said that “I’m proud about the process we have honed to work super closely to build these features with communities, not just for them. Wikimedia volunteers were involved from the initial user research through to giving feedback on designs and interactions with newcomers, and providing translations and advice.”

Bringing Wikipedia to mobile devices

The explosion in smartphone usage beginning in the late 2000s heralded a sea change in how people accessed information online, and the Wikimedia Foundation adapted to this new reality. We first introduced a mobile-specific version of English Wikipedia in mid-2007, followed by an iOS app in August 2009, and an Android app in 2012. By December 2015, mobile devices surpassed desktop pageviews on Wikimedia sites for the first time.

The Wikipedia apps have been revamped several times to improve their usability and functionality. As part of those efforts, we’re proud to note that Google called our Android app one of the best in 2015, and Apple named the iOS Wikipedia app an Editor’s Choice in 2017.

Jazmin Tanner, Lead Product Manager of Wikipedia Apps, said that she’s most proud of how customizable our apps are. “They really try to honor our diverse movement and that people may want to experience the beauty that is Wikipedia in different ways,” she said. For example, you can create a list of articles to share, read them in a distraction-free focus mode even while offline, get content from multiple languages in a single feed, and swap between themes. We’ve emphasized equity and accessibility in our app design, giving as many people as we can the ability to access and learn from Wikipedia’s knowledge.

Wikipedia’s visual identity

Another Foundation focus over the last twenty years has been improving Wikipedia’s visual design. We first overhauled Wikipedia’s look in 2009 through the Usability Initiative, which Mashable credited with bringing the encyclopedia into the 21st century.

In 2019, the Foundation’s Web team began an effort to update Wikipedia’s desktop interface for a new generation. “We need to provide not only excellent content and an experience that is engaging and easy to use, but also [one] that is on-par with their perceptions of a modern, trustworthy, and welcoming site,” Principal Product Manager Olga Vasileva said at the project’s beginning.

We prioritized equity in this work by conducting user testing and listening to a global population of people, opening dialogue in as many languages as we could. We also worked with Wikimedia volunteer communities to discuss our plans at length, and continued gathering feedback after the launch to refine those changes. We launched this work across 2022–2023, and you can see all the changes we made in this comprehensive rundown.

Building a tool to simplify translating between Wikipedias

Finally, did you know that the Wikimedia Foundation enables projects in upwards of 300 languages? “No other large internet platform or company supports as many languages as we do, and we’re really proud of that,” said Selena Deckelmann, the Wikimedia Foundation’s Chief Product and Technology Officer. “We take on this work because it’s extremely important to be able to access reliable information in your own language.”

To help Wikipedia’s knowledge be better distributed across its various language editions, we designed and built the Content Translation tool. Since being released in 2014, it has helped people translate over one million articles.

The tool works by automating a few tasks to make the translation work of Wikimedia volunteers both easier and faster, allowing them to close knowledge gaps between languages with ease no matter what device they are using. We are continuing to improve it; for example, since 2019, the tool has leveraged AI to share more knowledge with more people.

Removing governmental and legal obstructions to sharing knowledge

One of the major barriers towards achieving our mission is the ever-present threat of government or legal action that may limit access to knowledge. “Projects like Wikipedia do not happen in a vacuum,” our General Counsel Stephen LaPorte said. “It’s important to advocate for public policy that enables the Wikimedia projects to thrive.”

Whether a government limits access to Wikimedia sites, proposed legislation threatens to impact how we operate, or a Wikimedia volunteer is legally threatened, our Legal department advocates for the interests of a free and open web. They also defend us from the many legal challenges that can come with operating a top-ten website made entirely of user-generated content.

Protesting the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA)

One of the first times the Wikimedia Foundation took action against proposed legislation was in 2012, after members of the US Congress proposed the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA). We believed, as our then-General Counsel Geoff Brigham put it, that SOPA “earned the dubious honor of facilitating internet censorship in the name of fighting online infringement.”

One of SOPA’s stated goals was to reduce incidents of copyright infringement. But fighting that by forcing places like Wikipedia to find and remove all links to entire websites, even in cases of minor infringement, was a step too far. In response to these concerns about SOPA’s potential impact, English Wikipedia volunteers extensively discussed how they might take action alongside others. After thousands of words of debate, they decided to ‘black out’ the site for 24 hours, a tactic previously used on Italian Wikipedia in 2011.

On 18 January 2012, Wikimedia Foundation staff gathered at our office in San Francisco to enact the decision of those English Wikipedia volunteers. Erik Möller, the Foundation’s Deputy Director at the time, shared what it was like to prepare for that moment:

It was incredibly intense leading up to the point of the blackout because we knew we probably just had one shot at making a difference through an action like this. It would either fizzle and not be noticed beyond some news headlines, or it would really make a difference, possibly a critical one among all the internet protests of the time.

Our goal was to melt the congressional phone lines, to get the general public to care about an obscure law nominally about copyright infringement. Brandon Harris’ blackout design was iconic; if I stare at it for a few seconds it still gives me chills. Combined with an instant ZIP code lookup of your elected [US] representatives, the Wikipedia blackout did get people to pay attention and to pick up the phone.

In the end, when the Wikimedia movement came together with allies around the internet to support the free and open web, SOPA’s supporters indefinitely shelved the bill.

Challenging the National Security Agency (NSA)

Among the Wikimedia Foundation’s core tenets is the protection of user privacy. When you access Wikipedia or the other Wikimedia projects, we deliberately collect very little data about you. Unlike many other major websites, we do not track your activities elsewhere online. We believe that privacy is an essential part of the intellectual freedom at the heart of Wikimedia’s projects. As Jimmy Wales said, “It’s your own human right to be able to learn with privacy.” The Foundation’s Privacy policy and practices have long upheld this belief.

In 2015, we pursued this ideal off the Wikimedia projects and into the courtroom. Leaked documents revealed that the United States’ National Security Agency was targeting Wikipedia, among other popular websites, to collect personal data on internet users. We—and Wikimedia editors—feared that people would change their reading and editing habits now that they knew the US government might be watching; later research showed this fear to be true. With representation from the American Civil Liberties Union, the Wikimedia Foundation and eight co-plaintiffs sued the NSA in 2015. We fought for eight years to stop the mass surveillance of Wikimedia users.

In 2019, the case was dismissed; the NSA argued that the case could not proceed without revealing sensitive information about national security (this is called the “state secrets” privilege). We petitioned the US Supreme Court in 2022 to hear the case, but they refused. Still, the battle to stop mass surveillance continues in the US Congress, where we are working with allies to oppose the practice when it comes under consideration later this year.

We will continue to take action when the privacy of Wikimedia readers and editors is threatened. We may not win every case, but we can hold our own practices to a high standard and strive to protect users’ data—and maybe make the whole internet a better place.

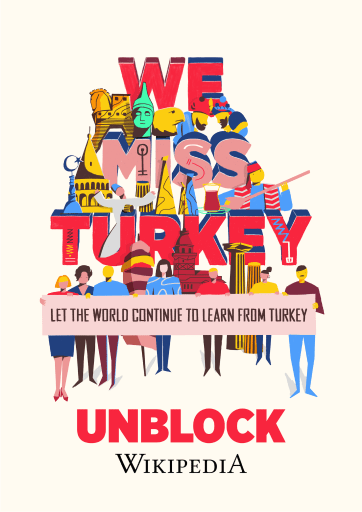

Unblocking Wikipedia in Turkey

On 29 April 2017, the Turkish government blocked access to Wikipedia. In a single moment, as former Senior Communications Manager Sam Lien wrote, “an entire nation suddenly went silent on Wikipedia.”

“My fellow Wikimedians and I were baffled,” said volunteer Başak Tosun. “At the beginning, I was thinking that all this was the result of a misunderstanding. I was sure that Wikipedia would be unblocked in a few days.”

Unfortunately, that was not the case. While the Wikimedia Foundation promptly initiated legal action to combat the block within Turkey’s court system, they took years to reach a verdict. This not only deprived Turkish citizens of Wikipedia, but denied the world knowledge, history, and culture from Turkey.

“We believe that information—knowledge—makes the world better. That when we ask questions, get the facts, and are able to understand all perspectives on an issue, it allows us to build the foundation for a more just and tolerant society,” former Wikimedia Foundation CEO Katherine Maher said in 2019, reacting to the long block.

Eventually, the Turkish courts ruled in our favor. Access to Wikipedia within the country was restored in January 2020, on Wikipedia’s 19th birthday. Threats of country-wide blocks against Wikipedia do continue, and our legal team often mobilizes to meet these new risks.

What’s next?

Over the last twenty years, the Wikimedia Foundation has grown to support the needs of volunteers and readers around the world, and this blog merely scratches the surface of everything we’ve accomplished. Still, our core mission of bringing the sum of all knowledge to all people has never wavered, and it never will.

“When I joined, the Foundation was a small organization with big dreams it could not hope to realize,” said Maggie Dennis, Vice President of Community Resilience and Sustainability. “It still has big, ambitious dreams, but now it is better staffed to set and meet big goals, and importantly to collaborate more closely than ever with our amazing international communities on fulfilling those dreams together. I used to love that we would shoot for the stars; now I love that I believe we can make it.”

This is difficult work. Our mission will not be achieved in the next day, month, or even the next decade. As the Wikimedia Foundation’s CEO Maryana Iskander said, “The practical realities of doing this in so many different languages, communities, and places feels like work that won’t be finished even when the Foundation turns 50.”

But we’re in it for the long haul, and we have a guiding light in an ambitious and long-term strategy built by and for Wikimedia volunteers. In the immediate term, we will shift our focus to respond to the needs of an ever-changing internet and build up relationships ourselves among the Wikimedia volunteers we work alongside. We will center our work around product and technology and prioritize knowledge equity in decisions, improve the experience of users, continue fighting back against the scourge of misinformation, and sharpen our effectiveness.

“We have made meaningful progress toward our really powerful vision of sharing the sum of all knowledge, and we welcome all who want to share in that vision with us,” said Iskander.

Twenty years ago, the Foundation came into being with a few servers and some committed volunteers helping patch up lines of code. At the time, we had no idea what it would take to gather the sum of all human knowledge. Two decades later—we still don’t know, but we are part of the largest movement of knowledge seekers and contributors in the world, all working to find out, together.

Over the coming months, we will begin an initiative to document the Wikimedia Foundation’s past—but we can’t do it alone. We invite anyone, particularly former staff, to contribute suggestions to this new Foundation timeline—launching and available for translations today in celebration of our 20th anniversary.

Originally posted by the Wikimedia Foundation to WikimediaFoundaiton.org on June 20, 2023.

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation