Since 2019, files on Wikimedia Commons can be enhanced with multilingual and machine-readable structured data. This addition brings many benefits for cultural institutions or GLAMs (Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums) partnering with Wikimedians, as GLAMs also store data about their collections in very structured ways.

In the past year, I have worked together with GLAM staff and Wikimedia community members to ‘test’ this new technology, and explore its potential, in a series of pilot projects. What does Structured Data on Commons make possible, and which new questions and challenges appear?

- We have imported the collection of a small museum to Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata, in order to experiment with data modeling and to explore the potential of structured data to make small collections accessible online for the first time.

- Community members have developed a micro-contributions game (the ISA Tool), testing the potential of ‘easy’ structured data editing for newcomers.

- Wikimedians have described digitized books with structured data, to prepare them for transcription on Wikisource, investigating how Structured Data on Commons can help to avoid data duplication across Wikimedia projects and how it can make cross-wiki workflows more efficient.

- Various organizations researched data synchronization and roundtripping with external databases – a feature that many larger GLAM institutions ask for, and for which structured data on Wikimedia projects provides more advanced foundations.

All these GLAM pilot projects have been described in earlier blog posts – click the links to learn more!

Connecting the world’s culture

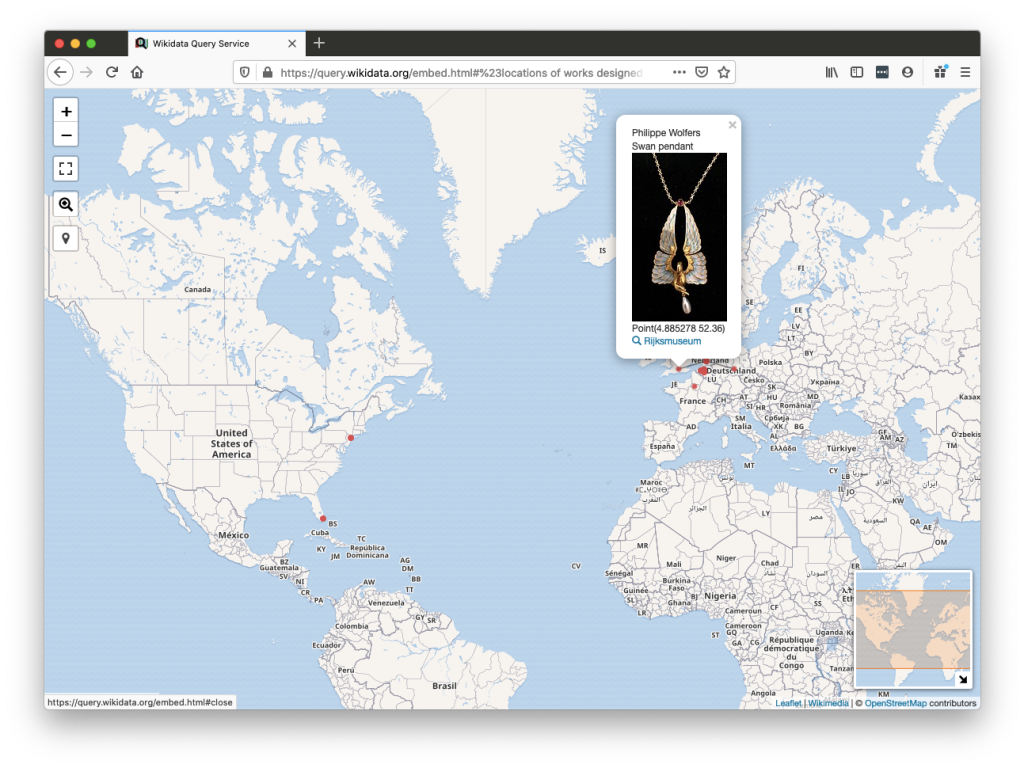

A fifth pilot project – Project Wolfers, described in more detail below – has explored the potential of linking various collections through structured data on Wikimedia Commons (and Wikidata). Why? Individual cultural institutions take great care in preserving and presenting their own collections, but these collections are not ‘islands’. Many art patrons have broad cultural interests: they may be fans of individual artists or cultural movements which are spread across collections around the world. Exhibitions, research and publications about human culture usually describe broader themes and developments. Online, non-profit cultural aggregators like Europeana, the National Digital Library of India, Trove (Australia) and the Digital Public Library of America, and private initiatives like Google Arts & Culture, bring individual collections together, and show connections between them. Culture fans often turn to Wikipedia for general introductions to cultural phenomena and the work of individual artists. Can the free and community-driven structured data on Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata help to strengthen this landscape and to make it it more sustainable? Wikimedia’s structured data offers an open, commons-based ‘connective tissue’ for the world’s digitized culture, and many Wikimedia community members are eager to support cultural institutions to make their collections more visible and discoverable online.

Wikimedia volunteers have explored structured data’s connective potential for many years already. Founded in 2014, the Wikidata project Sum of All Paintings aims to create a Wikidata item for each notable painting in the world. At this point, with more than 450,000 paintings on Wikidata, this dataset is starting to become large enough to discover patterns and create interesting visualizations – although this exercise will still be very biased, because many art collections around the world are not represented on Wikidata yet.

Passionate Wikimedians are also describing the sum of all video games on Wikidata, the work of sculptor Henry Moore and painter Edvard Munch, and entire art catalogs. Thanks to the international Wiki Loves Monuments competition, Wikimedia Commons now contains high-quality and free photos of the protected, built heritage of the world.

Developers can freely use the openly licensed, machine-readable structured data of Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons to build applications – and many do. Art and culture applications and websites, based on Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons, offer diverse ways to look across collections. A specialized example is the Astrolabe Explorer, a Wikidata-driven website for astrolabes around the world, created by Martin Poulter in his capacity as Wikimedian in Residence at the University of Oxford. Other examples include the all-round culture websites Crotos and Open Art Browser, and the interactive Wikidata-driven timeline that is built into the website of the Museo del Prado.

In Project Wolfers, a recent GLAM pilot project for Structured Data on Wikimedia Commons, the potential of structured data to describe the ‘sum of’ a topic (and its context) has been explored at a small scale, with a focus on decorative arts. As mentioned earlier, paintings and buildings already receive significant attention on Wikimedia projects, but there is still a lot of potential in highlighting other artistic and cultural genres – think performing arts, folk art, new media art, textiles, clothing and fashion, printmaking, and decorative arts.

Project Wolfers: three generations of Belgian silversmiths and their broader cultural context

Louis Wolfers (1820-1892), his son Philippe Wolfers (1858-1929) and grandson Marcel Wolfers (1886-1976) were the most well-known members of a family of prominent Belgian silversmiths and visual artists. From the mid-19th to the mid-20th Century, they gained international fame with their exclusive sculptures and pieces of decorative arts (tableware and jewellery) in the fashions of that period: from revival styles to Japonism, Rococo Revival (or Neo Louis XV), Art Nouveau and Art Deco.

Louis Wolfers père et fils: Teapot ‘Le Maraudeur’, 1890, collection DIVA. Photo CC BY-SA 4.0

Philippe Wolfers: Study of flowers, 29 May 1895, collection King Baudouin Foundation and Royal Museums of Art and History. CC BY-SA 4.0

Philippe Wolfers: Design drawing for the vase ‘Peacock Feathers’, 4 November 1899, collection King Baudouin Foundation and Royal Museums of Art and History. CC BY-SA 4.0

Philippe Wolfers: Vase ‘Peacock Feathers’, 1899, collection King Baudouin Foundation and Royal Museums of Art and History. Photo by Paul Hermans, Public Domain

Philippe Wolfers: Swan pendant, ca. 1901, collection Rijksmuseum. Photo CC0.

Philippe Wolfers: Nike brooch, 1902, collection King Baudouin Foundation and Royal Museums of Art and History. Photo CC BY-SA 4.0

Marcel Wolfers (1886-1976) also became known as a (quite prolific) sculptor. He contributed to various Belgian war memorials and public artworks. This is an excerpt of a relief sculpture by him, part of a large WWI memorial in front of Leuven’s train station. Photo by Jean Housen, CC BY-SA 4.0

The very diverse oeuvre of the Wolfers dynasty is spread around many museums and private collections around the world. How, then, can you get a broader overview? Several catalogs thematically describe the family’s output, and various large exhibitions have brought together the artists’ work. But there is no website yet which brings their oeuvre together across collections (and shows it in its broader context!). With this pilot project, we wanted to build the foundations for this.

In 2019, PACKED, Belgian centre of expertise in digital heritage (now renamed to meemoo, Flemish Institute for Archives), contributed data and images of the Wolfers’ oeuvre from four Belgian collections to Wikimedia projects: Design Museum Gent, King Baudouin Foundation, Royal Museums of Art and History, and DIVA, the museum for diamond, jewelry and silver in Antwerp. In addition, Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons already contained quite a bit of information about works from other collections as well.

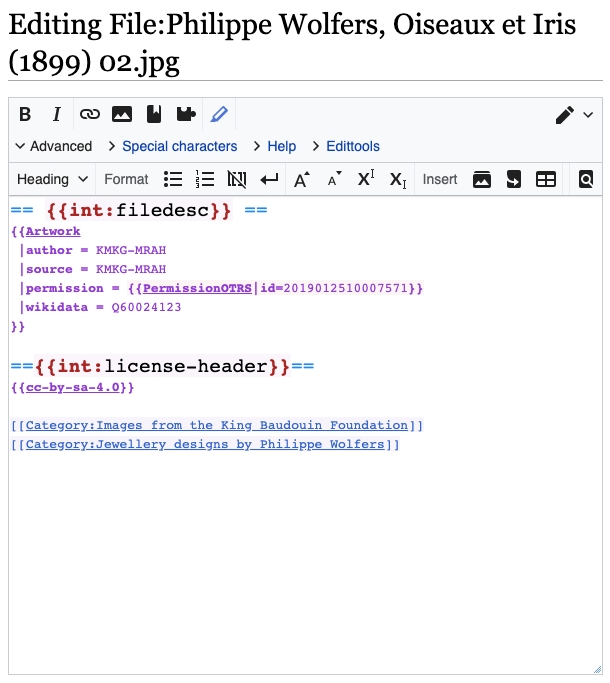

Like in the Jakob Smitsmuseum pilot project, PACKED team member Olivier Van D’huynslager uploaded (meta)data about works to Wikidata, and images of works to Wikimedia Commons. After the upload, the images on Wikimedia Commons were described with structured data.

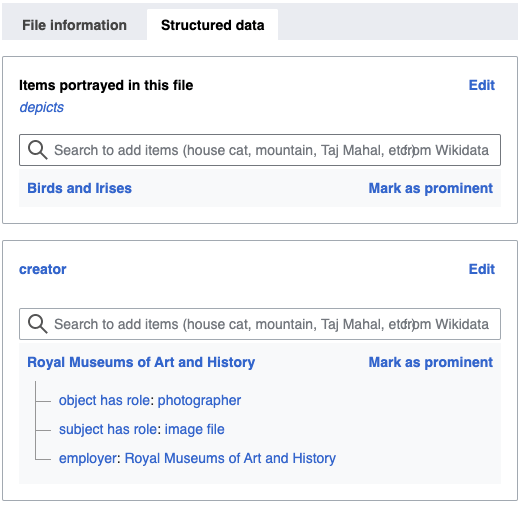

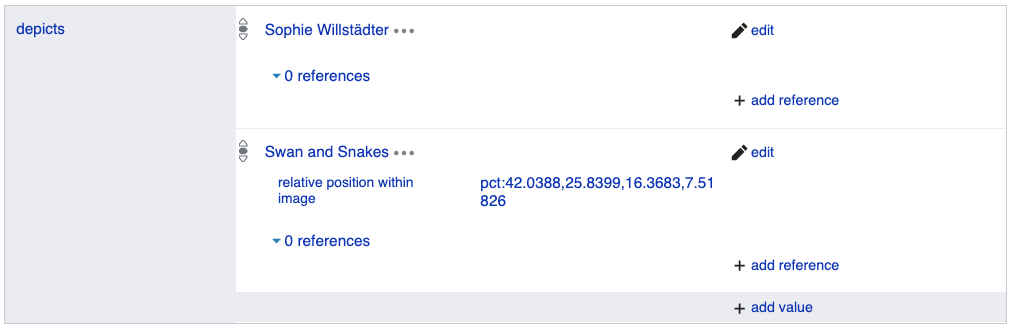

Some of the structured data of the file on Wikimedia Commons: a photo of ‘Birds and Irises’, a brooch/comb designed by Philippe Wolfers. Note that the structured data describes the file itself, and points to the artwork’s Wikidata item via the ‘depicts’ statement.

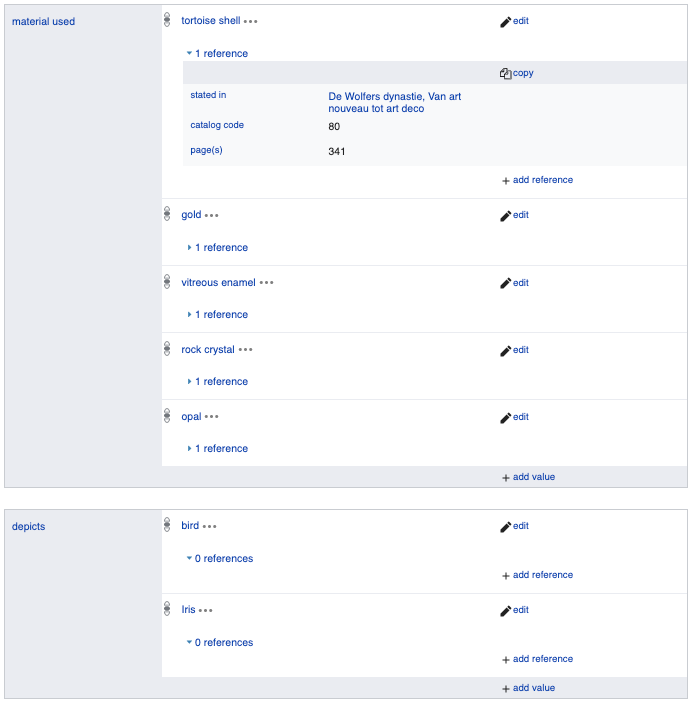

And some of the structured data of the Wikidata item of the object itself. Here, you find information about the materials used in the object, and the things depicted in it.

The example describes this photo. Philippe Wolfers: Birds and Irises, 1899, collection King Baudouin Foundation and Royal Museums of Art and History. Photo CC BY-SA 4.0

The Wikitext source of this image file on Wikimedia Commons. Note that the {{Artwork}} template is very short and takes most of its data from Wikidata.

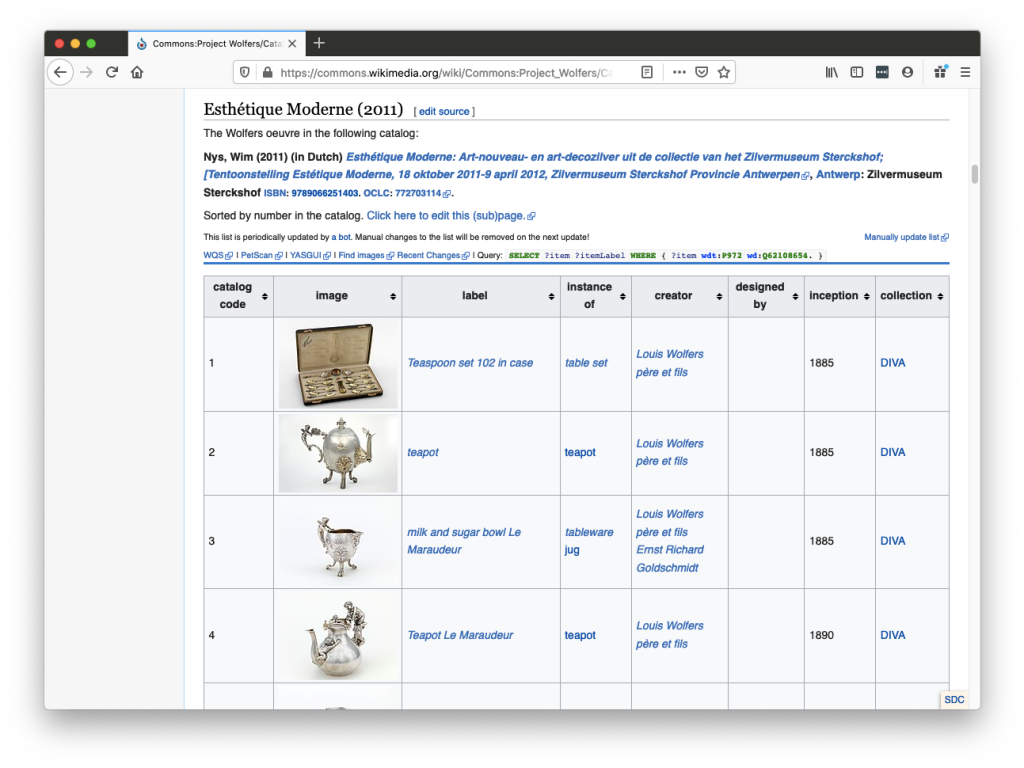

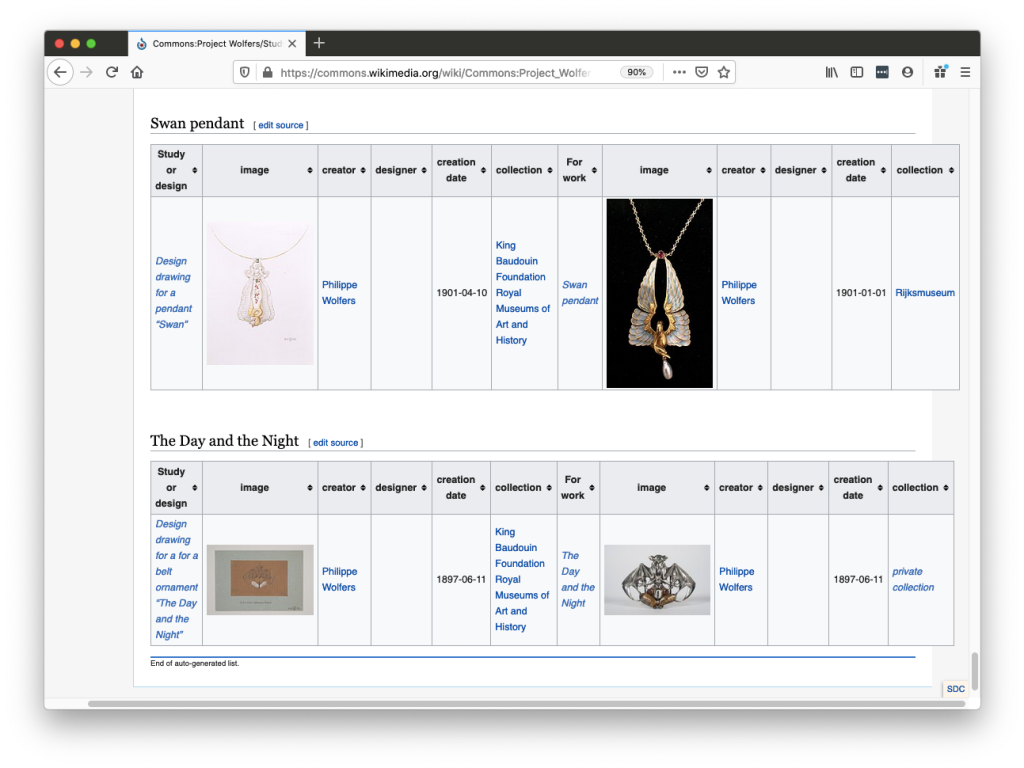

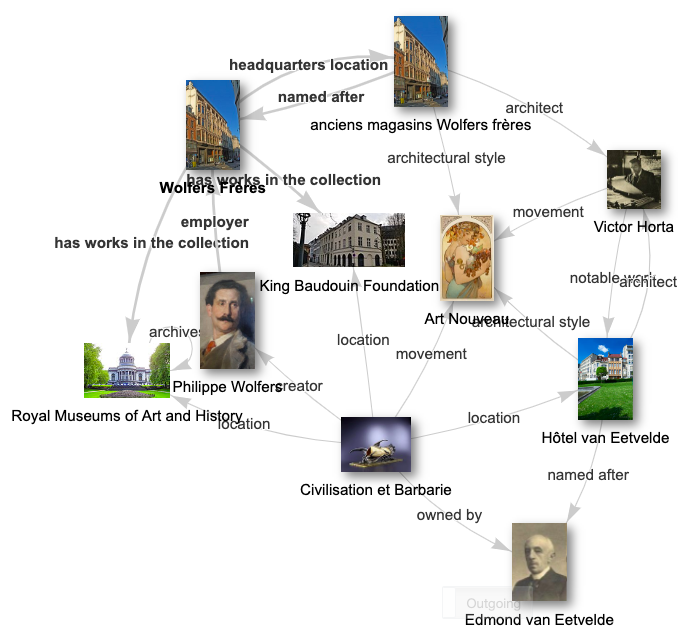

As a next step, we explored ways to show the ‘bigger picture’ of all these works, and to visualize connections between the works and images. We used the Listeria tool, developed by volunteer Magnus Manske, to generate dynamic, Wikidata-driven overview pages on Wikimedia Commons. You can check the various tabs on the project page, Project Wolfers, to explore them.

This rather small subset of very ‘dry’ data contains links to a broader context and story. The Wolfers dynasty was active in a lively artistic and political circle. The family’s firms employed many skilled workers and designers. The world-renowned Art Nouveau architect Victor Horta designed the family’s company’s flagship store, housed in a building in the center of Brussels. And some Wolfers designs are not just a display of wealth of Europe’s upper classes, but also intricately linked to Belgium’s fraught colonial history. Such stories will be told in Wikipedia articles that cover individual artists and artworks, but they can also be gleaned from the connections between data items on Wikidata. As a generalist knowledge base about the world at large, Wikidata contains plenty of ingredients to tell such a ‘data story’.

Firmin Baes: Portrait of Sophie Willstädter, 1903, collection Royal Museums of Art and History, Public Domain. In this portrait, Philippe Wolfers’ wife wears ‘Swan and Snakes’, the unique pendant that her husband designed for her.

The piece of jewelry shown in that painting: Philippe Wolfers: Swan and Snakes pendant, 1899, collection King Baudouin Foundation and Royal Museums of Art and History, photo CC BY-SA 4.0

‘Depicts’ statements of the Wikidata item of the abovementioned painting

If you want to experiment with similar visualizations (‘graphs’): the very recently developed Knowledge Grapher tool (built by Andrew Lih) will help you to generate them.

Structured data for copyright and licenses

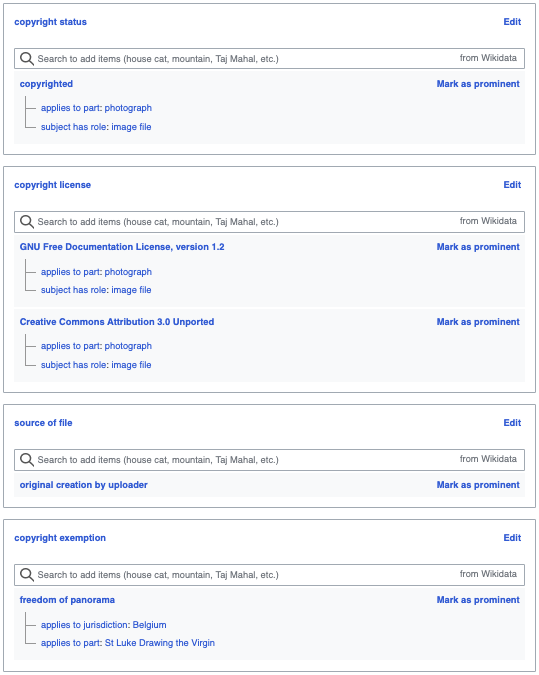

In addition to this broad exercise on interconnection and context, this pilot project also looked at a quite specialized area of structured data which is of primary importance for online GLAM content: intellectual property.

In the past few years, several Wikidata volunteers – most importantly User:Jarekt and Hanno Lans – have designed a data model to describe copyright statuses and licenses in structured data. This model (work in progress!) is documented on Help:Copyrights on Wikidata and already applied to many Wikidata items. In the context of structured data on Wikimedia Commons, it’s important to keep in mind that creative works, and media files representing these works, can have different copyrights, especially when a creative work is three-dimensional and it has been photographed from a specific point of view.

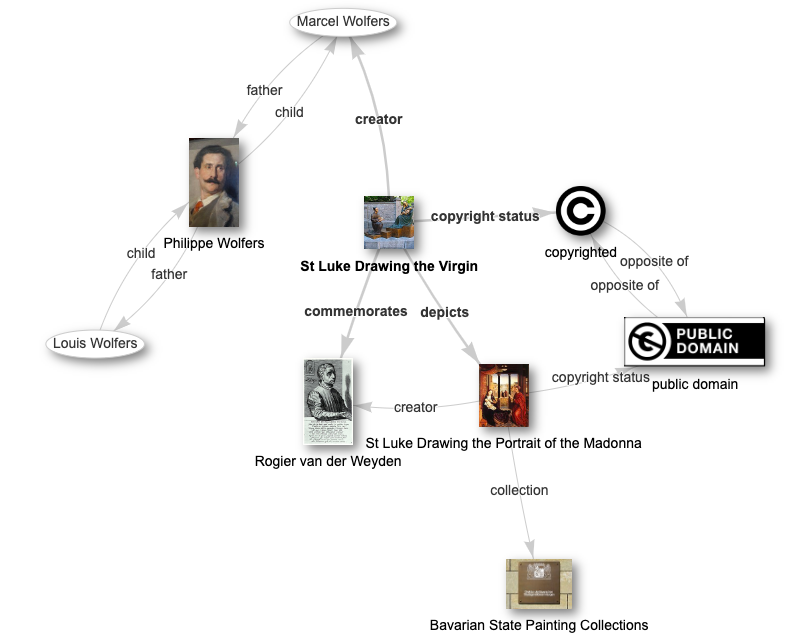

As an example, the work of Marcel Wolfers (1886-1976), the youngest member of the Wolfers dynasty, is still copyrighted; this is the main reason why Wikimedia Commons contains very few images about his oeuvre. There are a few notable exceptions, like this very interesting (copyrighted) sculpture (itself based on a 15th-Century painting in the public domain). Freely licensed photographs of the copyrighted sculpture can be uploaded to Wikimedia Commons because Belgium has Freedom of Panorama since 2016.

A particular sculpture in Tournai, Belgium: Marcel Wolfers: Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin, 1936. Photo by Jean-Pol Grandmont, CC BY 3.0

Some of the structured data of this photo. Note that there is no ‘best practice’ yet for describing Freedom of Panorama exemption; this is only an experiment.

Graph that shows the connection between this sculpture and the 15th-Century painting it is based on, including the works’ copyright statuses.

Structured and machine-readable data about intellectual property, copyright statuses and licenses has a lot of potential for useful applications. In the Netherlands, Hanno Lans works for the non-profit initiative Copyclear, which uses structured data from Wikidata to analyze entire GLAM collections and to perform copyright analysis on them. Structured copyright data is also being investigated by Creative Commons, as a component of international infrastructure to help institutions and end users determine and understand the copyright status of works, as discussed in a session at the Wikimania 2019 conference.

The above examples of structured data modeling are not exhaustive, and are still very much open to improvement. Feel free to edit the items and files, and participate in the data modeling discussions on Wikimedia Commons. If you have any suggestions or ideas to improve the description of intellectual property of creative works in structured data format, feel free to add comments to the talk page of Help:Copyrights on Wikidata. On Wikimedia Commons, there is also a dedicated talk page to discuss structured copyright data for media files.

Many thanks to PACKED, Olivier Van D’huynslager, Sam Donvil, staff of the participating museums, and OTRS volunteers from the Dutch-language Wikipedia, whose hard work, dedication and enthusiasm have made this pilot project possible.

This is part of a short series of blog posts on Wikimedia Space about GLAM pilot projects with Structured Data on Wikimedia Commons. Earlier posts are:

- Introducing ISA – A cool tool for adding structured data on Commons by Isla Haddow-Flood

- How we helped a small art museum to increase the impact of its collections, with Wikimedia projects and structured data by Sandra Fauconnier

- How can Structured Data on Commons, Wikidata, and Wikisource walk hand in hand? A pilot project with Punjabi Qisse by Satdeep Gill

- Data Roundtripping: A new frontier for GLAM-Wiki collaborations by Sandra Fauconnier

Can you help us translate this article?

In order for this article to reach as many people as possible we would like your help. Can you translate this article to get the message out?

Start translation